earthmoss

evolving our futureChapter 6 : Athens to Rome - My Enemies Enemy is My Friend

Contents / click & jump to :

- 01: Who is the Fairest of One of All?

- 02: Homer’s idea that poetry brings ‘undying fame’ to the hero is not his at all

- 03: Greece

- 04: The Emergence of the city states

- 05: Oh, MY, God!

- 06: Greek Philosophy

- 07: History in the Making

- 08: Survival of the Fittest – The Dance of Artifice

- 09: The Father of Everything – Natural Warfare becomes Unnatural War

- 10: Awe- Sacrifice Becomes Value-in-Exchange – as Honour

- 11: Trade versus Honour

- 12: The Tray Game of What is Not – The Via Negativa – The Ring of Gyges

- 13: The Arms Race Begins War in Reality – Not as a Story of Glory

- 14: How to Hold Power with or without Gods authority

- 15: Back to Reality – The Three Pigeons meet the Three Muses

- 16: The Back-Ground to the Peloponnesian War and its Players

- 17: My Enemies Enemy is My Friend – The Persian War necessitates – The Delian League

- 18: Karma – Self-Interest versus state-interest, the Pupil of Socrates Goes to Persia

- 19: Bad-Faith

- 20: Spartan bad-faith

![]() Note: When displayed, this icon indicates ‘Writer’s Voice’ style in text.

Note: When displayed, this icon indicates ‘Writer’s Voice’ style in text.

01: Who is the Fairest of One of All?

The Race of Gold, the Race of Silver, the Race of Bronze: Zeus made them, then despaired of them. The Race of Iron was no different. Their crops drained the goodness from the land, their fishing plundered the sea, and their cities weighed heavy on the Earth’s surface. They cut down tress for firewood, and they made more noise than a pack of apes in a bucket.

The Race of Gold, the Race of Silver, the Race of Bronze: Zeus made them, then despaired of them. The Race of Iron was no different. Their crops drained the goodness from the land, their fishing plundered the sea, and their cities weighed heavy on the Earth’s surface. They cut down tress for firewood, and they made more noise than a pack of apes in a bucket.

So Zeus resolved to reduce the number of mortals on the Earth. All it would take would be a single golden apple and the help of the Immortals- though he told them nothing of what he was planning. He gave the golden apple to Eris, god of strife, and Eris took it to a wedding.

All the gods and goddesses were there, the naiads and nereids, the dryads, the satyrs, and the centaurs. Dionysus had brought the wine, and no one begrudged the bride and groom an eternity of happiness. They had left at home their petty rivalries, and brought instead their sweetest smiles to the wedding.

No one saw Eris take out the apple and drop it casually to the ground. But everyone saw the apple.

For the fairest, said the inscription.

“How kind”, said Hera, smiling round her in a queenly way.

“Oh, but surely- it’s meant for me”, said Aphrodite, goddess of love, brushing her hair back coyly. “I mean, I presume…”

“You presume too much. You always did”, said Athena, putting her foot on the apple so that Aphrodite should not pick it up.

“I claim the apple.”

The wedding guests murmured their own opinions. Then they all began to quarrel about who was fairest.

“Zeus the Shining shall decide!” declared Hera, already thinking how best to make up her husband’s mind for him.

But Zeus refused. “Judge between my wife and my daughters?

Impossible! Ask a mortal to choose. He’ll be impartial. And let the most handsome decide the most fair. Which is the handsomest youth on Earth, would you say?”

On that no one disagreed. In every alcove and bower, goddesses, nymphs and mermaids- even the bride- sighed the name “Paris!”

Paris was the Prince of Troy – an alarmingly good-looking boy who had not yet fallen in love. Hermes, messenger of the gods, was sent to fetch him. One moment he was alone, fishing on the seashore, the next he was blinking at the brightness of the Cloudy Citadel. Before him sat the three most powerful goddesses in the word, carefully arranging the drapery of their gowns. “Look, don’t touch,” Hermes whispered in his ear. “And above all, Paris, listen. It may be to your advantage.”

As Paris passed in front of Hera’s throne with its golden eagles, she bared her teeth in a smile and whispered, “Decide in my favour and I shall make you the ruler of empires.”

“Thank you”, said Paris. “How kind.”

As he passed in front of Athena, she struck the pavement of Heaven with the butt of her spear so loudly that Paris started. “I see it now”, she whispered, glaring at him with her solemn grey eyes. “I, goddess of battle, whispered, glaring at him with her solemn eyes. “I, goddess of battle, see the crown of a dozen glorious victories round your brow! What battles won’t I win for the man who proclaims me fairest of all!”

“Thank you”, said Paris, and gave her such a dazzling smile that she dropped her helmet.

By the time Paris reached Aphrodite, goddess of love, he was learning the rules of the game. “What will you give me if I award the apple to you?” he said.

“What every mortal man wants most”, she murmured, puckering her fulsome lips. “The love of the loveliest woman on Earth.”

Paris did not hesitate. He laid the apple in Aphrodite’s lap… then ran for his life as sandals and spears came flying after him.

So Aphrodite won the apple, and she was true to her word. She gave Paris the love of the most lovely woman on Earth: Helen. There was something she failed to mention, however: Helen was already married.

But then, that was Zeus’s plan. When fair Helen laid eyes on Paris, she fell in over instantly and completely. Her husband was forgotten: all questions of right and wrong dissolved as she fled across the sea to the home of her handsome prince. As she fled to Troy.

In his rage and grief, her husband called on the King of Greece for help. The King called on his friends and allies to join forces with him and go after Helen- to make Paris and Troy pay for stealing her away. An army of thousands mustered their fleets of fast black ships, and prayed to the gods for success.

Now the gods, too, took sides.

“Oh yes,” said vengeful Hera, “I’ll help defeat Paris.”

“No”, said Aphrodite, “Paris must have his Helen. I’m for Troy.”

“So am I!” said Apollo. “There’s a princess in Troy I’m particularly fond of.”

“Well, I shan’t rest till Troy is in ruins and the Trojans face down in the sea”, said surly Poseidon. “I asked them for wages for building their precious walls. They told me they had a war to pay for, no money to spare. I’ll make them pay for that.”

For Athena the choice was harder. Troy, like Athens, was dedicated to her- its greatest treasure was a statue of her which the Trojans called the Luck of Troy. And yet Paris must pay …

All the mortal world took sides in the Wars of Troy. And above them the gods, too, ranged themselves for or against the Trojans or the Greeks.

Zeus looked down from his seat of power and watched the Earth bristle with columns of marching men. The nights twinkled with the fires of blacksmiths forging weapons. Shiploads of horses rode on the high seas.

It was his chessboard, all set up for the Great Game. With the unwitting help of the gods, the Wars of Troy would go on for years, killing men by the hundred, by the tens of hundreds- and women and children too. The Earth would be eased of weight of human feet, the fields and woodlands left fallow. Everywhere would be washed clean in a tide of blood.

It was the perfect plan.” (McCaughrean:2005:86-91)

“A third, suddenly re-orientating view of these relationships appears in of all places, the Old Testament. Just at the moment the Greek King Attarissiya was raiding Anatolia and Cyprus, in the thirteenth and twelfth centuries BC, and establishing settlements which archaeologists have been uncovering in the last few decades, the cities around Gaza in southern Canaan were taken and occupied by people whom the Jews called the ‘Philistines’. They had been drawn to the markets and the grassy downland of southern Palestine, where beautiful pear and almond orchards surround the mudbrick villages and where cattle and horses can graze on the clover and young barley of the open plains. Their lands- Philistia- are now the gentle, hilly farmland of south-western Israel. ‘Philistine’ in Hebrew means ‘the invader’ or ‘the roller-in’, and from the style of their rock-cut chamber tombs, the pottery they made once they had arrived in Canaan and from the form of their own names, it looks as if these Philistines, arriving from out of the west, were Mycenaean Greeks, cruising the Mediterranean seas, searching out new lands, ready to fight whoever they found there.

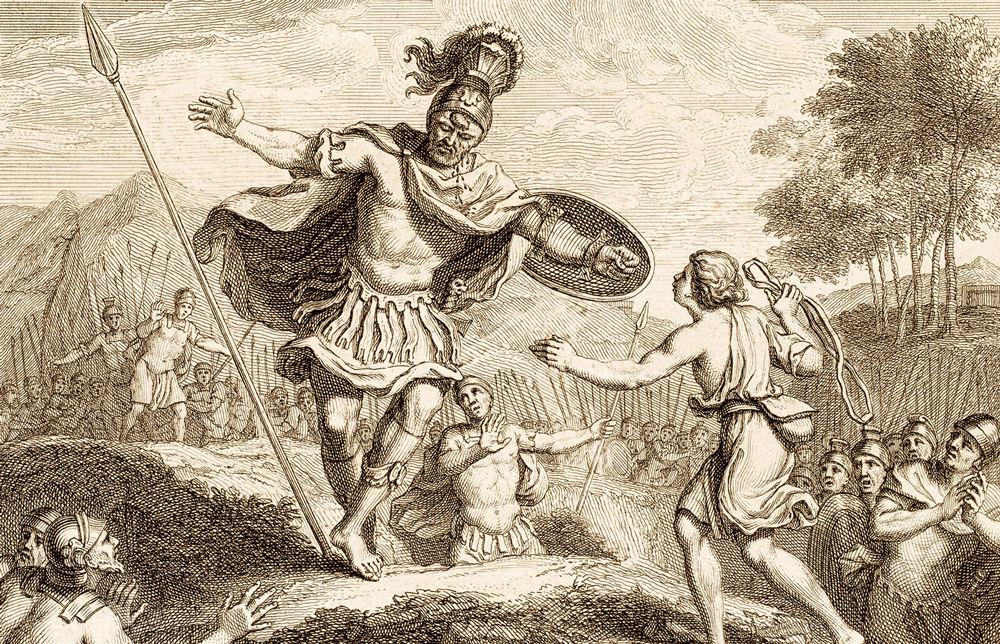

The war in Canaan between Greek and Hebrew was long and grievous, but at its symbolic climax, as depicted in the First Book of the Prophet Samuel, the readers are treated to one of the most hostile depictions of Homeric warrior culture ever written. The Philistines had taken up position on a hillside at Socoh in the rolling agricultural country of the Judean foothills, a few miles west of Bethlehem. A champion come out of the Philistine camp, a man called Goliath, to challenge the Israelites drawn upon the opposite hillside.

Goliath is a huge, clumsy, half-ludicrous, threatening and contemptible figure

David fights Goliath.

He is, even in the earliest and least exaggerated manuscripts, six feet nine inches tall, wearing the full equipment of the Homeric hero: a bronze helmet on his head, bronze armour on his chest, bronze greaves on his legs and carrying a sword and dagger of bronze…..

Massively over-equipped, a cross between Ajax and Desperate Dan, Goliath stands there shouting across the valley at his enemies:

‘Why do you come out to do battle, you slaves of Saul? I am the Philistine champion; choose your man to meet me. If he can kill me in fair fight, we will become your slaves; but if I prove too strong for him and kill him, you shall be our slaves and serve us. Here and now I defy the ranks of Israel. Give me a man’, said the Philistine ‘and we will fight it out’.

The front row stolidity of the Greek, his philistinism, his need to spell everything out, to put his own self-aggrandisement into endlessly self-elevating words- all of that comes out of Goliath like the self-proclaiming spout of a whale. But this is exactly what in the Iliad one Greek warrior after another liked and needed to do. Shouted aggression, the Homeric haka, was the first act of any Greek battle.

‘When Saul and the Israelites heard what the Philistine said, they were shaken and dismayed.’ It was not in them to make the symmetrical response- you shout at me, I’ll shout at you- which is one of the foundations of the Homeric system. …

When Saul, the king of the Jews, finally accepts that David might respond to the challenge of the Greek giant … it is a version of the Homeric arming of the hero and the single-combat meeting of warriors, the monomachia between Paris and Menelaus, Hector and Ajax, Achilles and Hector, which anchors the whole of the Homeric experience. But this is more like a parody of it than a borrowing. The unprotected boy, with his shepherd’s bag and stick, crouches down in the brook running between the two embattled hillsides, and with his fingers in the water, picks out the plain smoothness of five good stones. No love affair with bronze, no sharpness, no self-enlargement. In everything David does, and in every lack he suffers, there is one implied and overwhelming fact: the god of the Israelites. …

This is the view of the Greek heroism given us by the Hebrew scriptures: weak and bombastic compared to the clarity and strength of the pious mind.” (Nicolson:2014:223-27)

“Poetry itself supports that idea. Across the whole of the Indo-European world, echoes and repetitions of shared attitudes and phrases continually resurface. Scholars have pursued Homeric phrases through an entire continent of poetry and have come up with a set of attributes which seem to stem from those early beginnings.

02: Homer’s idea that poetry brings ‘undying fame’ to the hero is not his at all

It appears in exactly that formula in Iranian and northern Indian epics. Heroes with kleos or klutos, the words for fame or glory, built into their names are known in Greek (Herakles means ‘the fame of Hera’,..) but also in Indo-Iranian, Slavic, Norse, Frankish and Celtic. …

Poetry and war are joined in this: both are fame businesses. The same epithets are attached to these fame-seeking heroes across the whole enormous continent: he was ‘man-slaying’ in Ireland and Iran, and ‘of the famous spear’ in Greece and India. He stood as firm and immovable in battle as a mighty tree in Homer, Russian and Welsh. Like the Greeks, Irish heroes raged like a fire. In Anglo-Saxon, Greek, Vedic and Irish, that rage could emerge as a flaming flaring from the hero’s head. Proto-Indo-Europeans saw the great man as a torch. Across the whole of Eurasia his weapons longed for blood, even while this bloodseeking vengeance-wreaker was to his own family and clan, wherever they might be, the ‘herdsman of his people’ and their protective enclosure. There were no city walls in this world; the hero himself was their protection and their strength.” (Nicolson:2014:170)

“Whether it is Victorian India, Tenochtitlan, medieval Bohemia, shogun Japan, the world of The Leopard or Bronze Age Anatolia, this is the air breathed in any court, dense with rank, title, glamour, precedence, and surely a hint, here and there, of what is called, even now in palaces, Red Carpet Fever: excitement at being connected with the royal.

That self-importance surfaces in Homer in the overbrimming superciliousness of the Phaeacians, condescendingly welcoming the ship-wrecked seafarer Odysseus to Alcinous’s regal halls. The Phaeacians ‘never suffer strangers gladly’. They don’t like him much, nor he them. Even here, as he is accepting their hospitality, Homer gives him the traditional epithet he shares with Achilles and Ares the god of war: ptoloporthos Odysseus- city-ravaging Odysseus.

They guess he might be captain of a ship full of men who are prēktēres- an interesting word, with its origins in the verb for ‘to do’, meaning that Odysseus comes over to the Phaeacians not as a nobleman who can play athletic games but as the leader of a band of practical, pragmatic practisers of things, merchants in other words, dealers, or as Robert Fagles translated it ‘profiteers’, freebooters who blurred the boundary between trader and pirate.

Nothing irks Odysseus more powerfully than the suggestion that he is merely a sea-robber or tradesman. Is he not a hero? Has he not fought at Troy? Has he not suffered at sea? But the suspicion won’t go away. When he and his crew find themselves facing Polyphemus the Cyclops, the same idea recurs. ‘Strangers, who are you?’ the Cyclops asks them. ‘Where do you come from, sailing over the sea-ways? Are you trading? Or are you roaming wherever luck takes you over the sea? Like pirates?’

Perhaps this is a reflection in Homer of a reality which the poems do their best to conceal. Odysseus and the other Greek chieftains might think of themselves as noble kings, the fit subjects for epic. Homer does its best to portray them as that. The civilized states of the Mediterranean saw them as anything but. What were they but the ‘much-wandering pirates’ Odysseus sometimes talks about, taking what they could from the wealth of the world around them, hugely status-rich in their own eyes, virtually status-less in the eyes of those they were coming to rob? It is exactly how Odysseus himself describes his behaviour as he leaves Troy. ‘From Ilium the wind carried me’, he tells the Phaeacians, ‘and brought me to Cicones.’ This was a tribe, allied to the Trojans, who lived at Ismarus on the shore of the Aegean, somewhere north of Samothrace. ‘There I destroyed the city’, he goes on quite straightforwardly, using a term to mean that nothing was left. ‘and killed the men. And from the city took their wives and many possessions, and divided it among us, so that as far as I could manage, no man would be cheated of an equal share.’ It is one of the moments in which Homer coolly reveals the limitation of Odysseus’s mind. Our hero thinks he is telling his hosts how excellently he behaved, ensuring that unlike Agamemnon he did not mistreat his men. But he is blind to the significance of the actions preceding this exemplary fairness, the piratical destruction of an entire city and the enslaving of its women.

Extract from Apocalypse Now, Dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1979.

The same uncertain status of the pirate-king lies behind one of Odysseus’s most famous sleights of hand. He and his men are suffering at the hands of the Cyclops. The Cyclops wants to know who Odysseus is. In his answers, he says that his name is ‘Nobody’.

The Greek for that is either outis, which sounds a little like Odysseus if spoken by a drunk or slack-jawed giant; or mētis, which also sounds like the Greek word for cleverness, craftiness, skill or a plot. When Polyphemus calls for help, the other Cyclopes ask who has hurt and blinded him. ‘Nobody!’ he answers, or ‘Cleverness!’ and so his friends- and the audience- can only laugh.” (Nicolson:2014:217-9)

The Cyclops is a one eyed creature who can see the nature of his own death as revelation, when being seen by Odysseus it is the Gorgon eye of prophecy that shows Odysseus his own death through this way of life, but Odysseus uses his cunning to cheat this fate, and that is what the capitalist market does as it watches the seeds of war being nourished in the wake of its piratical plunder that it likes to believe is trade but in fact is war in sheeps clothing, the wolf at the door.

Odysseus’ men go on to be trapped by luxury and desire and are turned into pigs by Calypso, who promises Odysseus perpetual youth and immortality. Calypso means the hidden one, and of course that hidden one is the ego within who believes in its own immortality, the denial of death, that allows its plundering perpetual youthful infantile desires to become the reality by which it lives, as a pig.

03: Greece

“Cretan religion was centred on a female deity, the ‘Lady of the Beasts’ (Potnia Theron), shown as a goddess standing between two rampant lions, and possibly also connected with an elaborate statuette of a woman in the act of grasping two snakes. We have evidence of rites of consecration and sacred symbols of sovereignty, horn-shaped objects and the sign of the two-headed axe, from which the name of labyrinth (from ‘labyrs’ axe) was given by the Greeks to the Cretan palace. …

At the head of the Cretan empire was the Minos, who ruled from Cnosses after establishing himself as the leader of the old tribal organisations and other local dynasties. The names and titles of the Minos, his priestly offices and divine attributes reveal the sacred character of the monarchy. Greek tradition, referring to the Minotaur, seems to imply an identification of the King with the bull-God, and we might infer from this a time when the Minos was believed to be an immanent god, like the Pharaoh. However, more precise and complete evidence than the confused Greek legends has made it clear that the bull-God was an anthropomorphic manifestation of a celestial being, the Zeus of the classical world, and the Minos was thought of as his chosen protégé, delegate and friend.

So it is clear that the Minoan monarchy had characteristics in common with those of Asia Minor and Mesopotamia, rather than with the Pharaonic system. This is made more clear by the fact that the King held in his office not for life, but for nine years only, a term which could be renewed if the pact between the Minos and God were renewed in a complex form of mystical communication between them which took place on a mountain-top. This periodic investiture emphasized the subordinate position of the Cretan monarchy to the will of an aristocracy of priests and army officers.” (Levi:1955:28-9)

“So clearly, legitimacy, in Crete, had a religious foundation in the sense that it was by God’s will that the King held power, and man’s duty was to obey the laws because they conformed with the will of God. But the monarch was always a man, and his position as the elect of God set him above other men without changing his nature. His inferiors in dignity and power received their authority from him, and with it part of his dignity: if the King wore three necklaces as a sign of his sovereignty, the commander of the armed forces wore one.

The power of Crete crumbled very soon after it reached its greatest splendour, because the Greeks who settled in the islands off the Aegean shores learnt navigation from the Cretans and added to this skill the vigour of their tactics in war. This was the Mycenean-Achaean civilisation, until recently known only through excavations, chiefly in the Peloponnese, while Homeric tradition, which had influenced the whole of classical Greek culture, was concentrated on a single episode: the Trojan wars.” (Levi:1955:30)

“In centres of population they built palaces, unlike the Cretan in being fortified, so that perhaps they should be called castles, with elaborate monuments and tombs. Their political organisation was based on the populated centres, villages or cities, over which there ruled a local overlord, the ‘Basileus’, who held authority from the ‘Anax’ or supreme overlord, whose position was like that of Agamemnon in Homer: Lord of the heights of Mycanae. Land was distributed on a graded system of ownership depending on social class. At the top was the warrior class, who were the aristocrats, followed by the local administrators, then the priests, the foot-soldiers, and finally the manual workers.” (Levi:1955:31)

“The Achaeans imitated the Cretans in the building of fleets; they drove Cretan influence out of the mainland and then, around 1450 BC, they occupied Crete. The Indo-European type of military order had its period of ascendancy; in about 1270 BC, after a long war, the Achaeans captured and destroyed Troy, and after twenty years occupied Cyprus, taking over the copper mines on the island. … About twelve years later a new race, the Dorians, fell on the Peloponnese from the north, destroyed Mycenae, and superseded the Achaeans as rulers of the Greek peninsula.” (Levi:1955:32)

“The civilisation of the new Greek invaders was founded on the pre-eminence of the warrior caste; their leaders wear their arms even in the grave. They lie enclosed in breastplates, shields as tall as themselves lie beside them, and of their life apart from war they have left only records of hunting, the fighting man’s amusement in times of peace. In such a society, as in Persia, the leader’s position above the rest depended on his superiority in war, and religion itself could only mark a military leader as one whom the gods considered their friend and worthy of their aid.” (Levi:1955:33)

“Only the belief that they needed the aid of the gods to gain victory linked the political life of a society like the Mycenaean with religion: the warrior-king of the Mycanaean era based his claim to power on his might and success as a fighter. He ruled not because the gods wanted him as their delegate, high priest and supreme judge, speaking with divinely inspired truth and justice, but because he was the most valiant and successful of the warriors, whom the gods assisted by allowing him the military supremacy which was the origin of his power.

This, then, was a world of ethical, political and religious concepts quite different from those of Babylon and Assyria, and although the same fundamental characteristics had existed in the Hittite and Persian monarchies, the pressure of tradition and the influence of the Asiatic environment had led these to lose their original Indo-European characters, and to assume a fideistic and theocratic form.” (Levi:1955:34-5)

“The fall of Crete, in whose empire naval and commercial activities had been the most important, the return of piracy, and lack of security and the end of political unity all put the towns and villages of Greece at the mercy of the army, which defended and at the same time subjugated them. … The ordinary people continued to live in the world bequeathed to them by Crete, clinging to such religious beliefs as the divinity of the creative power of nature, venerated in the cult of the Minoan and Mediterranean mother-goddess, the Great Mother or Potnia.

The cult of physical perfection was, however, something new, arising from the ideals and aims of the military Mycenaean state. The Homeric poems reflect the life of the Achaean overlords of that time: the mighty warrior caste, now securely dominant, aspiring to a nobler state, struggling to secure for itself the position that had belonged to the Minoan monarchy….

The Achaean form of unity of fighting groups was the factor that determined Greece’s position in the eastern Mediterranean

The Trojan expedition, and the colonising journeys of the Homeric heroes who returned from Troy, remained afterwards in men’s minds as a nostalgic memory of a happy and glorious time, and proof of what the Greeks could have done if they had succeeded in co-ordinating their forces and had not dissipated them in brawls and raids on one another. In the Mycenaean-Homeric period the Greeks gained complete control of the Aegean and a firm foothold on the Ionian coast, strengthened by the Trojan victory.

As a result of the prosperity brought by their succession to the Minoan naval empire, the population of Greece began to find the supremacy of the warrior groups intolerable. The Achaean king was the prisoner of his army, and could only put forward policies which cited their interests as well as his own; he could not reform or extend the basis of his position.

In the richer, more civilized communities with greater resources, the groups which were just rising in the social scale were quicker to supplant the military upper class, and at the same time caused the downfall of the Mycenaean-Homeric type of monarchy, whose decline was due to the almost total disappearance of the fleets and of trade between the cities of Greece.

The aristocratic caste in its decline preferred to live on its stores of booty, and came to lack adventurers and active soldiers, while the naval power of the Phoenicians and the Greeks of the Ionian colonies created such competition that the mainland Greeks could no longer hold the command of the sea. At the beginning of the historical era in Greece, navigation was considered an occupation far inferior to the life of a small-scale farmer.

The development of this new rural capitalism completely transformed a society of semi-nomadic fighters into a state ordered in the interests of the landowners, who became the sole, or most important, means of production wealth for the community.

Following the social transformation, whose effectiveness varied from city to city, came a varied, but less rapid transformation of political life; centuries separated the evolution of power from the military to the landowning aristocracy in the different regions of Greece.

Whereas the old military aristocracy had enjoyed collecting gold and treasure, hunting, owning fine armour, the new land-owning class left to others the job of looking after their lands, and preferred to live in the city, imitating the wealthy classes of Asia Minor in their passion for the arts and for the cultured life; at one time military success and the booty of war were a man’s title to honour; now the new upper classes, with a different idea of human perfection, preferred athletic and intellectual prowess.

But the political situation remained in some ways unchanged. Military strategy still depended on the warriors in their chariots, cavalry and heavy-armed infantry. All demanded a great deal of capital, for armour and for buying and stabling the horses, and so only the rich could provide the army that the state needed….

So their wealth gave the rich not merely control over essential products, but also the burden and privilege of military duty, the only way of safeguarding the community. Political and social power gradually came into the hands of those on whom the state depended for survival, and the closer the connection between the two, the more efficient was the state organisation….

Added to this was the bloodtie, which created a community with a tribal leader, ancestors, religion, and which, for reasons inherent in the religion, imposed duties and social relationships which cut across economic barriers. His place in the tribe determined a man’s rights and status, imposed obligations, created ties and bonds of solidarity according to religious custom.

So the laws of religion and consanguinity limited the social domination of the richest, and the political and military domination of the strongest. Public life remained based on the Indo-European principle of entrusting the government to the assembly of arms-bearers, and in transforming the military into the aristocratic government, leaving unchanged the powers of the council of elders. The arms-bearers believed, and wished it to be generally believed, that the gods had bestowed on them the right to supremacy. The landed aristocracy, however, had the authority to govern and make laws only when it was sure of a divine will guiding its decisions, and felt that the community was equally sure of the existence of divine laws to which its own legislation conformed.

This was the only justification of the privileges of the few. The masses saw the rich and aristocratic as superior human beings

The Greeks were used to the idea of heroes; human beings whose especial virtues made them closer to the gods than other men were, beings whose beauty, power, influence and cultivation made even their physical appearance different from that of other men. The aristocrats had curled and perfumed hair, elegantly trimmed beards, wore trinkets of gold, embroidered and quilted robes, armour which was more the work of the goldsmith than of the blacksmith. They lived in luxurious houses, competed in horse-races and athletic contests, accompanied their singing on musical instruments, and seemed to be so favoured by the gods that they need only concern themselves with being agreeable and living glorious and happy lives. The petty tradesman or farmer, who shivered with cold beneath a cloak that barely covered him, who lived on a few figs or olives and coarse bread, burdened with debts, without education or any of the comforts of life- how could he have failed to imagine that the aristocracy was a race nearer to the gods than to himself, a race which was divinely predestined to organise the state and everything in it to suit itself?

Thus religion became an instrument of power for the aristocrats, as it had been for the Homeric kings. But it also limited their power, for they were bound by it to observe the traditional principles of rights and obligations which could not be transgressed without arousing feelings of sacrilege. …

To make sure that in decision of general importance the Greeks should be guided by the will of the gods to act according to the universal principles of right and justice, Greek society had its characteristic institution, the oracle.

In Egypt the manifestation of the will of God was the word of the Pharaoh-God; in Mesopotamia the word of the delegate of the gods. In the Indo-European world there was no such direct way of discovering God’s will, and men had to use divination to understand the signs sent by God. Such practices were already known to the Hittites, and by various paths had reached the Etruscans.” (Levi:1955:35-41)

“Oracles were a constant feature of Greek life and religion, in common with other Indo-European races. A typical oracular institution was the one at Delphi, whose cult of Apollo had deep Dionysiac roots. The influence of the Asiatic Sun-God was felt in the Greek mysteries and oracles from the earliest times, and this determined the origin of the divinity of Dionysus, who was the Thracian and Greek manifestation of the Sun-God. …

While formal symbols of sovereignty still survived in order that their duties as priests should not be interrupted, oracles were arising in many places. Cities and states would consult them as much as individuals, wishing to know the gods’ will in order to conform to it. The Delphic oracle stood out from the others because of its universal character, as the union of two concepts of the same Sun-God, so that it was better able than any other oracle to correspond to the religious ideals of all the Greeks as well as the races who shared their civilisation.” (Levi:1955:41-2)

“The development of Athens, however, owed nothing to her military power, but was simply the domination by the greater settlement, with convenient access to the sea, of the smaller agricultural settlements….

The demand for sea trading also arose because of the development of agriculture in Greece; increasing concentration of capital in the hands of a few landed families led to the downfall of the small-scale farmer, and so to increasing reserves of labour for industry, shipping and trade, and for agricultural labour.” (Levi:1955:49)

“In the same way the pan-Hellenic movement centred on the Olympic shrine was essentially a unifying movement even though at one period it lost ground by comparison with the other great pan-Hellenic movement, centred on Delphi. But all these attempts at unification, even those which never became anything more than regional in their influence, held the seeds of a true pan-Hellenism, and failed to achieve it only because the people of that particular area lacked the force, or will, or self-interest to impose themselves on the rest of the country.

The efforts towards expansion by the Anthelian League were an attempt to impose an aristocratic and military supremacy on the Greek world. If it had succeeded, Greece would have been organised by these aristocratic clans, strengthened by a claim to legitimacy based on the will of Demeter of Anthele. The Peloponnesian supremacy of Corinth and Sparta was a joint effort of a military and agrarian aristocracy, and an economic aristocracy of sailors and merchants. Around the Peloponnesian powers and their shrine a compact, enduring group was formed, whose cohesion is showed by the importance of the Olympic Games in Greek life, by the high level of culture reached in the Pelopponnese, and by the powerful position held by Sparta and Corinth at the beginning of the Persian wars.

In the period before the Persian wars, Greek unity was founded on the influence and prestige of the two sanctuaries, Olympia and Delphi, which balanced one another in authority. They were the source of legitimacy, the one derived from the God of Heaven, the other from the God of the Sun. …

To understand this era it is important to see its political system as something quite different from medieval or modern schemes; it is comprehensible only as the synthesis of the Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Anatolian and Persian concepts of the theocratic monarchy with the customs and way of life of an Indo-European dominant caste from the north. The intervention of oracles in human activities, the sovereignty of a supreme God of Gods and men, were the solutions of a civilisation which had no idea of legitimacy apart from that deriving from the gods.

These considerations have very important results for the evaluation of the Greek Polis, a development which has aroused much interest and speculation among modern historians. Modern nationalist theory, and even the more precise ideas of recent federalist doctrine, has spread the idea that the Polis was the limit of Greek political concepts, and that by being unable to grow beyond it, they had not achieved the power that comes with unity until the Macedonian threat forced them to combine their resources.

The ineffectiveness, perceived by Thucydides, which was a feature of this period of Greek history, was thus the result of circumstances which did not have their origin in the Polis. The autonomy of the Greek states did not prevent their functioning as a unity in the oracular period, that is, from the end of the Mycenaean era to the Macedonian conquest; it was rather the deep divisions and differences, the parties, which were the reason for the tension and conflicts that disrupted Greece, for in similar circumstances even in a united state, even in those whose pattern of organisation we are most familiar with, men have struggled to impose the supremacy of a philosophy, a political ideal, the interests of one region or one class.

For a long time, the Polis and the unity of Greece existed side by side, for legitimacy was founded on the transcendence of certain deities who communicated with men through the oracles. Within this system the Polis was guided in the interests of the dominant class in it. When a particular class was predominant, like the aristocrats of the Peloponnese, the whole of Greek life was regulated by its particular bias. Opposition survived, but everywhere a homogeneous ruling class was to be found, guiding the individual cantons along common lines, taking its authority from the oracles, which gave utterances conforming with the policies of the ruling classes.” (Levi:1955:51-3)

“If the landowners were in power in a particular city, they would obviously not want the industrialists to obtain control, nor the sailors and traders whose aim was increased trade and who would, on an open market, have forced lower prices and therefore lower profits for the landowners. Similar elementary cases easily explain why certain cantons clung to their autonomy, but the situation could be much more complex. If a city governed by a landowning aristocracy found itself face to face with a trading and naval community, the interests of the two cities- economic as well as political- not only differed but conflicted, since every advantage to the one was a disadvantage to the other….

Greece was a country of such varying social and economic conditions that it was possible for the interests of one class to prevail in one centre, and of their opponents in another

What is more, certain communities, although quite outside the sphere of interests of these dominant groups, came to find themselves drawn into the quarrels of the most important cities, and forced into paths of development quite unrelated to their own interests.

The groups with different interests in Greek politics were similar to the factions of any period of history; their fierce competitiveness expressed the lack of common ground for co-operation between the various parties in Greece. In such a situation disagreement led to open conflict, and the local autonomy of the states was not adequately controlled by the pan-Hellenic ‘oracular state’, which lacked the authority to prevent differences of political interests and aspirations leading to and supporting civil war.

The idea, expressed by Thucydides, that the Greeks should have conserved their strength, and instead of quarrelling amongst themselves should have united in foreign expeditions, like the Trojan wars or the foundation of colonies, which brought profit to all, seemed to his contemporaries to be the expression of only one point of view: that of Athens, whose interests were in trading and the sea. For the Athenians the advantages of the conquest of new bases, and of territorial and commercial expansion, were obvious. They were not so obvious to the peasants and landowners of Attica, and non-existent for the areas where the economy was basically agricultural and self-supporting, where there was neither the need nor the opportunity for trade, and little industry or manufacturing. The broils between neighbouring cities, which modern historians, under the influence of nationalist theories, claim to have arisen sometimes, or even in every case, from the desire for ‘independence’, were in fact struggles for life, or at least for the survival of their own way of life.

‘Independence’ meant the need to prevent the price of cereals, the farmer’s meagre revenue, collapsing under an influx of foreign grain. So it was also the desire to avoid changing the way of life that was hallowed by tradition. A city’s mean jealousy of another might, instead, be seen as the defence of customary privileges, of the power of the ruling class and of the city’s own religious cult; it might be the desire for that particular god’s sanctuary to become the centre of a general Greek festival, and its oracle to make laws for the whole country for the benefit of all….

This meant that the Greek cities could develop so far as they were able along their own lines, and that each political growth could blossom for a while. But while one group or region was not likely to be able to impose its attitudes and interests of the strong, and allowed each community to find the form of government that best suited its own needs.” (Levi:1955:54-6)

“The long and complex task of expansion and conquest, the building of an empire ruled not by a king but by a nation, was transforming Greek life and opening up new political, social and economic prospects throughout the Mediterranean.

We have already discussed the origins of this development. The days of the warriors with their armour and their chariots had passed centuries ago and now the age of cavalry too was coming to an end. The hoplite infantry and the warships had become more and more important, with cavalry as a small subsidiary, so that the manufacturing and merchant class became more and more wealthy.

The aristocracy had made Greece great and prosperous, and a result of this had been to free a great part of the citizen population from its state of economic and social inferiority: its new importance in the army and in manufacturing correspondingly increased its political influence and responsibilities.

The first stage in the decline of the oligarchic aristocracy resembled that of the theocratic kings. Written laws had limited the kings’ powers to the administration of justice: new laws limited the legal privileges that the aristocracy had assumed not simply because of its powerful position, but because of the popular vision of the nobleman as someone superior to ordinary mortals, closer to the gods and under their protection.

As the conditions of the poorer classes improved, the theoretical gap between the two classes began to close, and the almost hero-like superiority of the rich was no longer accepted. Men began to challenge the traditional laws based on the idea that the rich and the poor were almost different species. They demanded written laws, justice by arbitration, and powers of legislation.

The causes of this crisis were complex, springing from the new social situation which developed from the new expansion in shipping, trade, industry, and the new contacts throughout the Mediterranean world made by Greeks as the dominant sea power.

The capital for shipbuilding and cargoes was probably put forward in the first place by landowning aristocracy itself, but the lower classes profited by it to improve their conditions, not only because they became better off, but because they acquired a greater importance in the life of the community; the labour of each man working as a sailor, trader or artisan was now an essential and irreplaceable element in the welfare of the whole society.

Together with new social doctrines came new methods of warfare, and therefore new systems of levying troops for defence and conquest. Ancient tactics made each warrior into a tower of metal moving cumbrously over the battlefield, fighting individually in a duel which was not much more than the collision of two lumps of matter. Now the Greeks had to adapt their fighting methods to accommodate enemies who used methods of attack and defence outside the scope of Greek tradition, to deal with both hand-to-hand fighting and the disposition of bodies of troops over large distances.

The larger contingents now levied precluded the use of the ‘heroic’ warrior with his burden of armour; the shield became small, the breastplate lighter, with leather used in place of metal in the less exposed parts. The soldier warded off attack with a long lance, and the individual weakness of the new arms was balanced by a new system of fighting which made the troops dependent upon each other, placing them shoulder to shoulder so that every man was partly covered by his neighbour’s shield, and the front rank presented to the enemy a continuous metal fence of shields, bristling with lance-points. Under this new system, the job of the richer citizens was no longer to provide themselves with heavy, and now obsolete, armour, but to maintain and train cavalry troops to support the infantry attack on its flanks. The effect of the new tactics was to make the infantry the decisive element in battle, while the importance of the aristocracy’s contribution diminished.

In the same period technical progress resulted in innovations in shipbuilding too, which had their political and social repercussions

The perfecting of a technique of navigation by sail allowed the cargo ships greater economy and independence, while the warships, which could not rely on sail, were built for greater speed. The hull was elongated and streamlined, the decks covered throughout their length, the number of rowers increased and set in ranks one above the other to create the classic Greek of man-of-war, the trireme. The whole ship was better adapted for long voyages and greater speed and momentum. These innovations, and the greater number of ships that Greek military policy now demanded, increased the importance of the poorer citizens who provided the labour, and assisted the rise of the middle class which the new Greek economy and policies were creating.

These groups, which for the first time were gaining a place in public life, could not be satisfied with a system of government still founded exclusively on an aristocracy that no longer contained within it all the essential elements of society.

But the political consequences of the new situation could never be the same throughout a land where local autonomy and profound differences of economy, environmental and social relationships prevented any sort of political uniformity. In some places the aristocracy defended its institutions and privileges, legal and religious, even using violence to oppose the middle and lower classes, who in their turn did not shrink from using revolutionary methods to assert their rights against the ancient legal codes. In such circumstances the only hope of a peaceful and legal settlement was the setting up of a new social order, using someone trusted by both sides as arbitrator, or giving him the more complex task of creating a new legislative foundation for the state, as the heroic founders of the colonies had done.

The arbitrator or legislator had to find a language which the local population would accept as expressing not merely the product of individual initiative, but truth of an absolute validity. This meant that he had to link legislation with religion, with the gods who were the source of authority; his method depended on the religious customs of the locality.

The legislator could himself assume semi-divine, heroic powers, or could simply be appointed to his job by an oracle, or else his actions and decisions could be held to be inspired by the oracle. But the developments of Greek religious thought could lead to yet other solutions: not only the soothsayer, but the wise man, the poet and the artist too could be divinely inspired, and their words could have the value of insights into the absolute truth of the mind of God.

Where the peaceful solution was possible, it was based on class relationships within the oracular state which were fluid enough to permit agreement without violence. In other regions the struggle was fiercer, and the privileged classes were attacked with a greater concentration of forces, under the guidance of a popular leader. Such conflicts were resolved not by peaceful agreement, but by the domination of the community by the middle and lower classes. Their leader did not hold the position of legislator or arbiter, but of executor of the revolutionary will of the people.

The power of a faction-leader who imposed himself on a community by force seemed to the Greeks to be an offence against the principle of the divine origins of authority. These leaders were called ‘turannoi’, a name which linked them with the military governors who commanded the garrisons in Asia Minor, marking their headquarters inside the fortifications and surrounding themselves with armed men. The image of the ‘tyrant’ was that of the usurper, holding power without legitimacy based on the laws and the will of the gods, but simply as a result of intimidation by force. This was an open attack on the Greek concept of the state as an organisation under the guidance of the gods, through the oracles. The tyrant did not act in the name of all, under divine guidance, nor by virtue of his transcendent gift of the knowledge of truth and justice. He imposed himself by the use of force, and substituted the will of an individual for the supremacy of an absolute truth, or as it has recently been defined as ‘the event’ for ‘the form’.

The tyrant in Greek history, however, appears as someone rather different from the governors, government officials and local commandants of Asia Minor.

There power was held by delegation, from God to the King, from the King to the official, and so conformed to the local idea of legality. But in Greece the name of tyrant marks the first example of power without divine authority to occur in the ancient Mediterranean world, as far as our limited evidence shows.

It cannot be said that the abnormal character of tyranny consisted in its denial of equality between members of the community. Such equality was continually being denied to men, and in a much more serious way. Any man’s pre-eminence over others, or comparison of himself to the gods, is a negation of human equality. The legislator, the hero, the colonial leader, were human beings who distinguished themselves from their equals by being chosen by the gods and divinely inspired. But according to the theory of the oracular state, in which all power must derive from the gods, this superiority was legitimiate, but that of the tyrant was not…. Authority belonged to God alone, and had done everywhere for thousands of years. To think that it could belong to any group of men, large or small, would be to imagine that the mass created by the union of a number of men could assume the nature of a transcendent being.

The tyrannies spread throughout the seventh and sixth centuries BC. It would seem as if the new crisis in class relationships in Greece had two possible solutions: that of the legislators and arbiters, within the bounds of oracular legality, and that of the tyrants, which was utterly beyond the pale.” (Levi:1955:61-5)

“The new class demanded as its first concession secure legislation on the matters that chiefly concerned it, and it is important to notice that this legislation contained no constitutional reforms for the community or the canto, that is, for the Polis. It is clear, therefore, that the new class was not interested in its political position, but only in its private, family, economic situation. So the ruling aristocracy was able to maintain its political supremacy, making concessions on matters concerning the individual. Where aristocratic resistance was more bitter and tenacious, one finds that the new classes had begun to have political aspirations; on other occasions they very resistance of the aristocracy provoked revolt, which they had to put down by using force, which led inevitably to tyranny. …

A notable feature of the history of the tyrants, and one that often appears at revolutionary periods in history, is that the men who come to power in the struggle with the aristocracies nearly all come from the same class themselves. When the political situation has been settled for a long time, the men who hold effective power and public office in the state belong to the privileged and dominant group which is, therefore, synonymous with the governing caste. But at times of crisis and revolution a new class which is rising, or hoping to rise, to power is unlikely to have at its disposal men with the ability to govern in its name and interest. So it happens that the governing caste can to some extent detach itself from the dominant class, since the old dominant class, like the new, finally has to use the same men to fill public offices.

In fact, the tyrants accomplished nothing more revolutionary than did the legislators…. Their instinct in legal matters was always to avoid open recognition of the fact that a revolution had occurred in the very sources of law and authority, and to display the trappings of traditional legitimacy in an effort to show that their own power did not contradict it.

In the interests of the classes that had raised them to power, they allowed them financial concessions and certain legal guarantees in matters affecting the individual and the family. In politics they managed to reduce the resistance of the aristocrats by dispersing or silencing the most active members of the governing caste. In economic affairs the tyrants to some extent preyed on the richest class either by heavy taxation or by legal actions followed by sequestration. With the money gained in this way the tyrants began public works which were a sort of aid to the poorest classes. Thus the policy of the tyrants at least in some places about which we have some information, succeeded in making life easier for the poor, giving them greater security and opportunities for work and production. …

Even Thucydides reproached the tyrants for the excessive chauvinism of their policies. The effect they had was to make their supporters rich, themselves more secure, and to commit their cities to ambitious public works which emphasised their independence of pan-Hellenic unity and encouraged enthusiasm for the success of the one particular Polis even at the expense of the others. On the whole the policies of the tyrants tended to damage the fundamental unity of the Greek people which aristocratic solidarity had supported with the help of the oracles. …

By the end of the sixth century BC the age of the tyrants was over in mainland Greece

But the disappearance of the regime, which had been the product of political crisis, did not leave all the various Greek communities in the same condition or do away with the differences that had made independence necessary. The cities were left more active and less inclined to any co-ordination of policies; they had every encouragement to grow apart.” (Levi:1955:66-9)

“In particular, the Lacedaemonian situation was different from any other, Sparta was not a local community ruled by an aristocracy, but a survival of the ancient system which had grown up after the Achaean conquest. The Spartans could never merge with the landowning aristocracies of the other Hellenic states. Their system of landowning, which was linked with the governmental organisation of the Homeric-Mycenaean conquerors of the peninsula, gave total possession of the land to the conquerors, reserving a part for the kings and their households and a part for the gods; the rest was divided among the conquering warriors, who cultivated it with the labour of the Helots, the expropriated inhabitants, and lived on the produce.

The situation in the colonies was no different: the leader reserved a part of the land for the gods and for himself, and divided the rest into equal shares for the colonists. This continuation of the methods of the Achaean conquerors in Greece created a political order identical with the one which the Spartans had preserved unchanged for many centuries.

Thus the Spartan ‘cosmos’, whose claim to political wisdom was the limitation of the citizen body to a small proportion of the inhabitants, was not the product of exceptional political wisdom and deep thought, but the fossilisation of a very ancient system, which had been developed to deal with the conflict of power and right at the time of the conquest of the Peloponnese.

Sparta preserved her original position while the rest of Greece moved on by cultivating a deliberate isolation. In particular family and business relations between Spartans and non-Spartans were forbidden. They did not want to concern themselves with industry or trade, and indeed the use of iron coins only when everyone else used silver impeded any sort of trade and made necessary a rigidly self-sufficient economy. …

So Sparta, in her artificial isolation, had undergone her own evolution, only in part in line with the rest of Greece: even in Sparta, in spite of the original, ancient equality amongst the Spartiates, there were differences between richest and the Spartiates, there were differences between richest and poorest, more and less powerful; the kingship had first been reduced to an office held by two magistrates, then abased to become an instrument of the assembly of the privileged.” (Levi:1955:69-70)

“In the seventh century BC Attica was not yet organised into cantons under the Athenian aegis. The city was completing its transformation from an ancient monarchy dominated by the landowning aristocracy to a state in which the aristocrats succeeded in retaining their political position at the expense of their economic and legal privileges. The result of the reforms in Athens was a substantial change in the conditions of life of the poorer classes. …

The aristocratic ‘Eupatridai’ of Athens survived the long parenthesis of tyranny, and by yielding to the economic pressures of the lower classes became a typical example of a governing body functioning without any attachment to the class from which its men came, or even conflict with it.

It was in fact men of the highest birth who destroyed the privileges of the great families, when this was necessary for the preservation and furtherance of the classes to whose prosperity the whole Athenian economy was now linked. The profits of the great as well as the small investors were at stake, and the aristocracy continued to rule only by putting into effect laws directed to the destruction of its own predominance and privileges. They were aristocrats who brought about the legal and economic reforms which gave protection to the lower classes, support for their financial enterprises, more humane debtor’s laws, and, little by little, concession by concession, full legal parity of all members of the citizen community, with no distinctions made for wealth or birth.

All the states during the classical era preserved the system of dividing the citizens into clans based on common descent, an arrangement which survived in even the most advanced social organization, as a means of determining and dividing amongst the citizens their duties and debts to the community as a whole, in such matters as military service, public offices and tribute. The rights of the citizen were proportionate to the value of his services; those who served in the army, or contributed more than usual to its upkeeping or effectiveness, or paid larger tributes, had rights denied to the rest. The changing conditions, which allowed the poorer class greater participation in the life of the community, made it necessary to cancel the clan-divisions based on birth or wealth, in order to put all citizens on an equal footing. New divisions were made, based on place of birth or residence.” (Levi:1955:70-72)

![]() Writer’s Voice: It’s the first godless magical womb theory of rights to not be culled and considered a human being because of a world of pure imagination or ideology with no legitimacy other than it benefits the sponsor to self-justify it.

Writer’s Voice: It’s the first godless magical womb theory of rights to not be culled and considered a human being because of a world of pure imagination or ideology with no legitimacy other than it benefits the sponsor to self-justify it.

“During the sixth century BC Sparta became the leading light of the Greek world, because of her domination of the Peloponnese and her alliance with Corinth. Her influence extended to the Delphic oracle, and so she had a means of imposing her will on the rest of Greece through the mouth of the god, and so giving her domination the aura of legitimacy. The Spartiates had become the fighting arm of all the well-born and wealthy groups which dominated most of the Greek cities.

The arts in all their forms helped to create an atmosphere favourable to the oligarchies of birth and prestige

It was not only the ancient heroic ideals, which failed to create a favourable impression in the modern context, but useful and effective new concepts that served the purposes of the oligarchs.

Poetry had developed into one of the most important influences on popular ideas. The vitality of Homer’s verse and its place as the foundation of the Greek system of education impressed its ideals of heroic virtue, physical excellence and valour, and its code of manners on generations of Greeks. Nor did the poems of Hesiod, who wrote in Boeotia at the end of the eighth century BC, in any way conflict with the vitality of the Homeric tradition: Homer created the image of the heroic and in every war superior warrior nobility; Hesiod described the world of the poor, men without any other concept of their destiny, content with what little good came their way, resigned to the many miseries and hardships which made up their lives on earth.

Hesiod’s world was not at odds with the world of Homer. It does not have the boldness of a new people claiming a great position in the state, but describes the life of the humble, seen by a man who has observed it at close quarters, understood it and taken part in it, with the simple conviction that in the world men cannot be equal, and the destiny of the humble is as necessary as that of the strong and powerful. If anything can assure the poor and insignificant that they are not debased to the level of slaves or animals, it is the dignity of labour and the awareness of a task honestly performed according to the will of the gods….

In the cities of Asia Minor and the islands especially, the heights and depths of men’s experience were expressed in poetry that exalted the individuality of man, whether it was Archilocus’ pride in the valour of the soldier and lover, or Hipponax’s contentment with the lazy, graceless, greedy life of a beggar.

It was still a world where men accepted wealth or poverty as something as inevitable and unchangeable as beauty or ugliness, physical perfection or deformity. … Mimnermus celebrated youth and love in poems which hold echoes of a society without cares or duties in the army or government, wanting only to enjoy a life made simple by wealth. Sappho too expressed in her love songs the feelings of this new spiritual aristocracy, which felt itself linked by its perception and discrimination, and found in arts a new way, apart from the traditional pre-eminence of the warrior or athlete, of rising above common mortals and approaching the gods.

In the social order of this society, in these centuries, nothing changed. Men preserved their fundamentally aristocratic idea of the natural domination of ordinary people by ‘their betters’, and their betters were, inevitably, the richest, since only they could excel in war, train for success in athletics, and get the education needed for distinction in science or poetry.

But when the political conflict reached the point of questioning the values of the aristocratic view of society, the voice of poetry reflected the change. When the upper classes, content with the privileges they felt to be eternal, just and divinely ordained, began to feel the pressure of the lower classes and the persecution of the tyrants, and saw the transformation of the world which had been organised to suit them, poetry became a cry from the heart, expressing passions and anxieties, rancour and hatred in a way that would not have been conceivable some decades before.

One poet, Solon, spoke with ancient wisdom and almost divine inspiration to invoke order and justice in a city torn apart by civil war. All men, he said, must be treated as humans, and their fury and desperation appeased. Unlike Hesiod, he recognised that the wretched man does not have to resign himself to his misery, and that the rich man does not have to accept his privileges, as if they were just and due recognition of his natural superiority.

A revolution was proclaimed in this poem of the sixth century BC, a revolution which the oligarchs tried to avoid by means of legislators and arbiters, but which often, when it was under armed leadership, they could not escape….

As long as the existence of a class of demi-gods was generally admitted, men born to be heroes and leaders, entrusted with the task of guiding and defending, succouring and caring for their flock like shepherds, it was easier to keep that flock content with its destiny and convince of its inferiority to the king and his peers. But when the differences between men were seen to be wealth and intelligence, it became clear that although success was due to divine will and inspiration, it was still open to anyone to be given that inspiration, and in any case there was no justification for oppression, injustice and exploitation. …

Although they no longer had kings, the Greeks did not feel that they were abandoned without guidance. The gods were present among them, living in the house-temple that derived from Mycenaean constructions, and were described in verse as intervening in human affairs. Their passions and emotions made them more like men than solemn idols. As the gods were invested with the appearance of human beings, the human form became idealised and minutely studied in an effort to re-create it worthily of its divine associations. So the archaic ‘kouroi’ and ‘korai’ were created. …With the passage of the centuries, the Greeks learnt the holy truth that an aristocracy like this was open to all who were worthy of it.

Athens learnt this secret and so assumed the historic mission which distinguished her from all the other Greek cities. Dominated by its aristocracies, Greece had a unity and uniformity, but Athens, for reasons inherent in her history and environment, detached herself from it to find her own solution to problems common to the whole of Greece.

In spite of Spartan domination and vigilance, the Athenians affirmed the full equality of all men in their relations with the Polis, and limited the powers of the old aristocracy until it was left in control only of the Areopagus, an organ of judicial and political character made up of those who had held the highest offices of state. Athens was becoming the ideal of the motherland to all who could not tolerate the rule of aristocratic oligarchies, and the natural enemy of all those who could not renounce the privileges of centuries. Within the Greek community the rise of a new vision of human society brought with it the beginning of a greater, graver disunion.” (Levi:1955:72-6)

“Persian sovereignty was based on religious principles which were utterly alien to the Greeks, and considered all those who were not Persians or Medes to be merely subjects without political rights, outside the community of free men. But the result of this was, as has been shown, absolute tolerance of the religious, social and economic activities of the subjects, so long as the king’s dominion was acknowledged and the tributes regularly paid.

Persia gave to the Greek oligarchies and landowning classes a surer guarantee of security to enjoy their way of life than did the new movements in Greek public life. Upper-class Greeks had already taken many habits and customs from the lands now ruled by Persia, and life in some parts of Asia Minor was now something worthy of imitation.” (Levi:1955:79-80)

America and the Cold War i.e. Marcos and Hussein, etc, etc

“When Greece declared war on Persia, two streams within the Greek community were fighting for control of the country. This conflict had been going on for many centuries, and followed a pattern found in every state; the conservative aristocrats, the class which in the past had held absolute power because its existence had been essential to survival of the community, versus a reforming movement of classes with less wealth than the aristocrats, but an increasing importance, led by men who claimed that only their policies had any real relevance to the state’s political and social needs.

So the war against Persia was more in the interests of the new middle classes than of the old upper class… The reform movements and the new classes themselves took credit for the Greek success, and this gave them a greater confidence and enterprise in the political battle.

After the victory, the aristocrats who had opposed resistance to the Persian invasion thought that once Persia had retreated across the Aegean they could come to an understanding which would guarantee peace, a new political regime, and the re-establishment of their own supremacy. Like some modern political parties, they could see no reason against forming an alliance with any foreign state that would help their own cause to victory.

Meanwhile the political conflict between the cities was becoming no less bitter than that already being fought out within the individual Polis. War had forced the two groups to declare themselves. Athens had witnessed the victory of a party that was gradually bringing about reforms in favour of a section of the population without privileges to preserve, but dependent on increasing its trade, its wealth and its political and economic opportunities.

The Greeks were victorious against Persia because they were fighting an army which had no vital interest in winning.” (Levi:1955:81-82)

![]() Writer’s Voice: The Liberals vs the conservatives or the liberal/conservatives versus the communists after this battle for power had been won by disenfranchising the poor and the Cold War begins

Writer’s Voice: The Liberals vs the conservatives or the liberal/conservatives versus the communists after this battle for power had been won by disenfranchising the poor and the Cold War begins

“There were also technical reasons for the Greek military success: the distance of the battlefields and occupied areas from Persian bases, the difficulties of communication, the doubtful valour under attack of some of the Persian contingents, Greek tactical superiority and understanding of the value of surprise, and above all the naval supremacy that she gained the course of the war.

No other factor in the Greek victory was as important as this last. Nor was it a new situation. For more than a thousand years ships and fleets from the Aegean had controlled the Mediterranean. Centuries of tradition accustomed the Greeks to looking on the sea as the road to power, independence and prosperity, and at the same time made of them experts in the arts of navigation and shipbuilding.

The Greeks and Phoenicians were the only nations which could dispute the supremacy of the Mediterranean, and the Persians had neither the fleets nor the tradition to make it even remotely possible for them to acquire naval power; moreover their religion forbad them to sail. So Persia was dependent for her requirements as an imperial power on her subjects’ fleets: after the Ionian revolt and the punitive destruction of Miletus she could not rely on the Phoenicians.

The growth and technical improvement of Greek naval power was the decisive factor of the Persian wars: especially as the creation of a great Athenian fleet, built up hastily during the two phase of the war, with a hundred ships under construction at a time, shifted the balance of naval power in favour of Greece: also the new Athenian fleet was a centre of attraction for all the Greeks whose interests coincided with those of Athens in matters of trade, expansion and the development of shipping.

Thus the war did not introduce new factors into the political situation, but was an opportunity for a rearrangement of the balance of power. The conservative, agrarian interests which had dominated Greece in the sixth century BC were still strong, for Sparta and her army were on their side, but now the opposition was also strong, for Athens and her fleet was behind it. …

At the end of the Persian wars Athens found herself at the head of an organisation of cantons which included all the greatest naval powers in Greece; she could have satisfied herself with an alliance leading to a pan-Hellenic hegemony.

The centre of the Greek state was always an oracle, the religious focus and source of political authority. There were many attempts to make Athene, the Goddess of the Acropolis, an oracular deity. The legend so commonly shown on Attic vases, of Heracles becoming angry with the oracle at Delphi and stealing the tripod, was a transparent allusion to the desire to make Athens the centre of the Greek oracles.

The most conspicuous result of the Persian wars was the Delian League. Not only was it the most important movement towards Greek unity in historical times, but it was also the basis of Athens’ claim to succeed Sparta as commander and guide- as ‘hegemon’- of all Greece. The choice of Delos as centre of the confederacy underlined the Athenian ambitions, for the island which was the birthplace of the sons of Latona was perhaps the only place in the Greek world that could possibly compete with the authority of the Pythian oracle.

So this was not a secession, but an imperialist, aggressive bid to strengthen a movement towards the conquest of the state” (Levi:1955:82-4)

“The Persian wars had scarcely ended before voices were heard denigrating the men who had contributed most to the victory; accusing them of disloyalty and greed for money; personal polemics backed up by accusations of secret agreements with the King of Persia, of thefts, personal ambitions, and duplicity rampant amongst the leaders of the two chief political movements. It cannot be denied that both sides hoped to find support from the King of Persia, now safely back in Asia Minor, which would help them to victory in Greece, since whether the movement favoured a conservative policy based on an agricultural society, or an expansionist trading policy in the Mediterranean, it was useful and logical to provide for a compromise with Persia, for neither policy was likely to harm her empire, and it would be to her advantage to be able to rely on a friendly Greece, without ambitions against Persian territory.” (Levi:1955:85)

“In Athens, in fact, some members of the old aristocracy had been forced, in order to retain their position in the governing body of the state, to act as the representatives of middle-class interests and aspirations, and to ally themselves with the groups which had recently become wealthy, landowners and industrialists, to defend themselves from the pressures put upon them all by the poor, to whom the naval policy had given an importance out of all proportion to the attention paid to their needs in the economic policies of the city.

The classes which equipped warships for the city now knew that their importance to the state was no greater than that of the classes from which the hoplites were enlisted. Equally, all the makers of cloth or pottery or metal goods or any other merchandise providing the city with trade knew that for economic reasons the city had to take them into account. But this was not what happened. The politicians paid little or no attention to these developments, and this political inadequacy to deal with social conditions created the situation from which, inevitably, revolutions spring.

In foreign politics, the poorer classes of the population wanted the greatest possible commercial and naval expansion, and this could only be achieved by breaking down Persian control of the Levant and driving the Phoenician fleet from the eastern Mediterranean, even perhaps from Carthage. Only this policy could provide work for all, a ready market, and cheap imports. But it was precisely this which the upper-and middle-class landowners were anxious to avoid, for they were afraid that the success of the lower classes would lower their own standard of living.

So the political conflict flared up all over Greece, for internal and foreign politics were inextricably interwoven. In Athens the struggle between reform and conservatism was kept within the bounds of party politics, but in the Peloponnese it led in the end to civil war. The resistance put up by the Arcadians forced Sparta to seek help from Athens. It was the speed and enthusiasm with which the conservative politicians in Athens embraced the Spartan cause, as well as the discourtesy with which Sparta treated the auxiliaries she had solicited, which created a tense atmosphere in Athens and started the democratic revolution there. …

The Athenian democrats and their supporters were bound to see the Athenian expedition to help Sparta as an act of hostility and oppression towards themselves by the conservatives aristocrats who governed them. To use the state’s armed forces in an enterprise against the interests and principles of a class that in any case thought itself undervalued by its rulers could only strain the situation to breaking-point. …

The Athenian expedition to the Peloponnese mobilised several thousand hoplites, that is, it removed from Athens several thousand citizens with safe incomes who were able to offer themselves for military service in the fully-armed infantry. This was a large proportion of the landowning middle class, which had been on the side of the conservatives ever since the Persian wars. This was the chance for the popular party to be successful in the public elections.

The chance was not lost, and the elections marked the end of the Areopagus as a political power, and the downfall of the conservative oligarchy. It was the beginning of a new experience, unique in the history of the ancient world, of a government body deriving its authority from the most numerous but poorest group of the population, the basis of the city’s wealth through trade and industry.” (Levi:1955:87-89)