earthmoss

evolving our futureChapter 10 : The early church sires the medieval

Contents / click & jump to :

- 01: Introduction

- 02: Constantine: 306-337 CE – a very brief biography

- 03: Seizing Power

- 04: The founding of Constantinople

- 05: Augustine sires a Violent Church from a Violent Empire

- 06: Mani and his Daemon – Remember the Fate of Socrates and his Daemon or Christ and his Angels?

- 07: Assassination is not as powerful as Sorcery – Bureaucracy is more powerful than Sorcery – Byzantium

- 08: Byzantium – Bureaucracy trumps Sorcery – the Democracy of Pyramid Theology

- 09: The End of Pelagius – The End of Early Christianity?

- 10: Donatism – The Death of Rome, the Rise of The Walls of the Church into a Pyramid – Constantine Gets Control of Christianity

- 11: The Law Versus The Word

- 12: Early Christianity its historical activities resultant from Augustine’s Theology and Rome’s Autodynamic laws of the right to self-perfection

- 13: Women in Early Church – not Augustine again! – Oh Yer!

- 14: A brief look at the Muslim tradition in relation to Women

- 15: The Christian temples of Antioch, Alexandria, Jerusalem, Constantinople, etc. displayed the ostentatious piety of a prince ambitious, in a declining age, to equal the perfect labours of antiquity

- 16: The sacraments of the church were administered to the reluctant victims, who denied the vocation, and abhorred the principles, of Macedonius

![]() Note: When displayed, this icon indicates ‘Writer’s Voice’ style in text.

Note: When displayed, this icon indicates ‘Writer’s Voice’ style in text.

01: Introduction

“We have to face the fact that the creativity we admire happened in an age that was quite as desperate and ugly as Gibbon saw it to be- an age of absolutism and terror, that fostered timorous conformism and blind ideological and sectional prejudice.” (Brown:1972:153)

“In Order that a Religious Institution or a State should long survive it is essential that it should frequently be Restored to its original principles.”

It is a well-established fact that the life of all mundane things is of finite duration. But things which complete the whole of the course appointed them by heaven are in general those whose bodies do not disintegrate, but maintain themselves in orderly fashion so that if there is no change; or, if there be change, it tends rather to their conservation than to their destruction. Here I am concerned with composite bodies, such as are states and religious institutions, and in their regard I affirm that those changes make for their conversation which lead them back to their origins. Hence those are better constituted and have a longer life whose institutions make frequent renovations possible, or which are brought to such a renovation by some event which has nothing to do with their constitution. For it is clearer than daylight that, without renovation, these bodies do not last.”(Crick:1979:385)

It is a well-established fact that the life of all mundane things is of finite duration. But things which complete the whole of the course appointed them by heaven are in general those whose bodies do not disintegrate, but maintain themselves in orderly fashion so that if there is no change; or, if there be change, it tends rather to their conservation than to their destruction. Here I am concerned with composite bodies, such as are states and religious institutions, and in their regard I affirm that those changes make for their conversation which lead them back to their origins. Hence those are better constituted and have a longer life whose institutions make frequent renovations possible, or which are brought to such a renovation by some event which has nothing to do with their constitution. For it is clearer than daylight that, without renovation, these bodies do not last.”(Crick:1979:385)

The creation of the Catholic Church and its theology that we have so deeply assessed in the previous chapter, was not established in a non-world but in a thrownness of worlding- that of the Roman Empire- that it ‘inherited’ upon its demise.

What we need to look at now is how this worlding of Catholicism took over from the Classical Roman worlding; how this was achieved and how the clash of the Republic and its territorial Empire changed the beliefs and practices of the Christian Church as it formed into this inheritor.

What we need to understand is how the Word of the Son of God, whose ‘tekton’ or organisational theory was one of universal love and peace, became the culture of violence and intolerance, headed by a singular divine office of the Pope in Rome. By doing so we will be able to chart the death of the heterodynamic experience of the soul, and watch it become autodynamic whilst stepping-in-itself to take the place of this homodynamic experience of being-in-Being, as will be more fully charted in the medieval times, from these early roots.

By understanding this journey then we can begin to understand the age of the medieval from its beginning and see its evolution and not as a conglomerate blob of the past that has no relevancy today, with knights and magicians, dragons and wenches, etc, etc, as the media represent it in order to entertain, or contain, us and our world concepts.

To do this we must first answer the following questions: Why did Constantine suddenly choose to make Rome Christian and how had the ideas of Augustine, that we witnessed in the previous chapter, translate themselves into the institutionalised perspective of the church and its subsequent behaviour to its flock and those outside of it?

To answer these questions we must look at the life of Constantine and Augustine and see how they come together over the Pelagian Controversy and the Donatist Controversy, that forced the power of Constantine and the hierarchy and structure of the Church to manifest itself into the institution that it became in the medieval period. As we will see the art of this manifestation served to increase the temporal power Constantine, of the Church, and of Augustine himself.

Religion becomes the cohering glue to defeat Constantine’s enemies, to gain and maintain the authority to possess the Empire- The necessity of Christianity as a State religion of unprecedented violence.

02: Constantine: 306-337 CE – a very brief biography

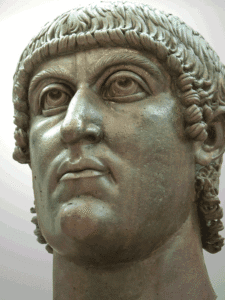

Constantine I, also known as Constantine the Great, was the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity.

What follows below is an annotated version of ‘I Caesar- The men who ruled the Roman Empire’. A BBC Documentary series. To save space we will look at Constantine but briefly before we see the more important parts of his contribution to Catholicism through the life of Augustine in much greater detail. For now I merely wish to prove that Constantine was using Christianity in order to gain power for himself, and not due to any great revelatory vision that he claimed to have had at Miluvian Bridge, as we shall see.

I believe that it will be easier to realise the impact of Rome and Augustine upon Christian conceptual thought and practice if we briefly walk in Constantines shoes from a historical perspective of the ‘movers and shakers’ lens before we move on to the more detailed history of this actual conceptual thought and then to see its resultant practice.

In the 3rd century the Roman empire is under siege. Persia in east is the most feared enemy, over the barbarians in west- in a world of war, where the emperor is now chosen by the armies of the frontiers and not the senate. His father supported Diocletian in a coup against the emperor, and won.

Diocletian as emperor now shares power with Maximian to keep empire, Diocletian is senior and rules East. Constantines father divorces his wife and marries Maximians daughter. Diocletian splits empire into four- the Tetrarchy-, and Constantines father gets one of these 4 territories centred around Trier in Gaul, becoming a Caesar. Constantine held by Diocletian as a hostage to maintain fathers loyalty, and so is brought up in the court of Diocletian.

Diocletian now sure that rule of 4 has stabilised empire with his organisational theory of the tetrarchy-, goes on the offensive against the barbarians and the Persians with Galerius leading the attack, a young Constantine rides along with him, making a name for himself in battle.

Diocletian didn’t want dynasties and had to watch Constantines rise, grooming him but also watching him.

2% of Rome is Christian under Diocletian, concentrated in the Greek-Eastern cities trying to get control of government. Glorious afterlife and expiation of sin found appealing by many Romans. Problem with Christianity was denial of existence of other divinities that had helped Diocletian regain his empire. AD 303 Churches demolished, bibles burnt, torture and executions under Galerius’ encouragement. Constantine watches the Christian commitment to their faith, as they die, and it this martyrdom courage and faith shown by them that impresses Constantine.

Upon the death of Diocletian, Constantines father is made Augustus of the Western part of the Empire and Galerius is made Augustus in East. Constantine is expected to become Caesar of a part of the Empire, but Galerius did not wish to set up a western dynasty and so he was not chosen. His father feared for his sons safety under Galerius, but Galerius refuses to release him from his court. What can his father do? Constantine runs away to Gaul to rejoin his father. Together they go to England to defeat Picts.

On 25 July 306 in York, England, his father dies. His troops declare Constantine Caesar of Britain and Gaul, Constantine accepts this illegal promotion and returns to Trier to consolidate his position in Gaul and the Western Empire and to increase his perceived legitimacy through victorious battles and increase his popularity in that area. Moving swiftly he declares himself against the persecution of Christians, and releases all of them from prison in Gaul. This brought him great popularity. “Here was a religion that might work for him.” he thought, and remembered the willing-ness and courage of those Christians he had witnessed being slaughtered under his mentor Diocletian.

He then attacks barbarians across the Rhine, to show ‘the might is right’ side of his rule. The kings of these barbarians heterodynamic tribes are captured and then killed in games by wild beasts.

In October 312 At Miluvian Bridge he marches on Rome to remove Maxentius, another usurper emperor who has taken over the majority of the Empire and Rome itself, during this time.

It is here that Christianity becomes Constantine’s stated religion for it is at the Miluvian Bridge that he has a vision, as he is about to ride into battle and kill his own people, for his own glory. Eusebius records his vision as, ‘a blazing light in the heavens, that formed the shape of a cross in the sky’.

Geologist Dr. Iain Stewart in his BBC One series- Journeys From the Centre of the Earth sheds some light on the possible truth of this vision that I feel obliged to incorporate before we look at the evidence regarding this visions truth.

Dr.Stewart cites an Italian legend of this same vision from a pagan perspective. A Tribe worshipping Cybele is recorded as having a festival in October 312 in which men dressed as satyrs with virgin girls dancing around them. They too saw a new star shining in the sky, getting nearer and nearer, until the ground shook violently and the dancers were knocked out cold. This folklore dates from 4th century and could be proof of Constantine’s vision. But of course not of its subsequent authored meaning.

Was it a comet? Well, 30,000 tons of space debris falls on our planet each year- these are shooting stars- meteors that completely burn up in the sky. If big enough to survive it is a meteorite. They produce a very particular type of dent on the Earth’s surface. An explosion on the ground that makes a round crater surrounded by debris, that falls close to the whole. In 2003 a group of scientists found a lake just across the mountains from this legends birth place, which was created around 4th century. Some geologists however think that this crater is in fact a giant ditch made by farmers?

In regards to the vision of the cross, the meteor impact would have created a Mushroom cloud, through which, illuminated by the light from the burning up of the meteorite as it entered the atmosphere, there could have manifested a cross of light in the sky.

Whatever the truth behind this now pagan and Christian ‘vision of God’, God picks a side and it is Constantines. For the Christians in the army this is inspiring, whilst the rest were persuaded that the emperors God would bring victory, maintaining cohesion through the power of the imperial cult instead. This victory gave the troops a powerful feeling of a new God being victorious against an old god, and Constantine is now Augustus of the Western Empire. Christianity is one step closer to taking Rome, but the Eastern Empire still stands.

In the east Galerius has died and been succeeded by a general Licinius who Constantine now marries his sister to in good old familist nepotistic heterodynamic mafia-like style.

Whilst in Rome he woos the public with vast building projects of public works- and holds a triumph for himself, building what will be, the last triumphal arch of Rome.

So is this Christian Constantine whilst still in possession of only the Western Empire proclaiming Rome Christian or is he keeping the pagan gods happy in some way too? Well whilst still remaining the chief priest of pagan belief, he then took on the role as head of the Christian church where he is expected to have a view and to arbitrate the hierarchy of this new Church. In other words he is either a hypocrite i.e. an actor using the Christians to gain power or perhaps more kindly he is just unaware that Christ is any different from the Logos that the Pagans have been worshipping anyway and sees no paradox in his roles as Pagan Ruler and Christian Ruler, whilst also being Pagan god, and Christian (conduit of God) the High Priest. Maybe talking to himself, through himself, about how he was a false pagan god and therefore undeserving of the authority and supernatural powers vested in him, whilst also being the conduit of the true God expected to set up the hierarchy of the Catholic Church through the authority of the vision and victories given to him by God in defeating the pagans who worshipped him as a god was a conversation that he felt able to hold with himself without any niggle of hypocrisy. Let us see how this god/conduit of God proceeds and judge him thusly, under the question, ‘Who Benefits’?

Determined to unite the Roman world Constantine breaks his pact with Licinius and marches on him. Through his role as champion of the Christian church he is being recognised by people in the East, where the threat of the Persians looms large, who hope that he will come to them.

At Adrianople he is wounded in the thigh, but still leads men to victory. Licinius withdraws to Byzantium where he is defeated and executed. It is a dirty civil war, seen as Christian crusade but really it is a ‘brutal unnecessary war’ against a good eastern emperor, it is, ‘a cynical piece of power grabbing cloaked in Christian terms’.

03: Seizing Power

His accession to power was, unsurprisingly, the result of his military victory over his rivals. In 305, Galerius became Augustus in the East and Constantius Chlorus in the West. For their respective Caesares they took Maximinus Daia and Severus. But in 306 the death of Constantius Chlorus (from natural causes) prompted the army in Britain to proclaim his son Constantine emperor. Reacting against this, the praetorians in Rome chose Maxentius, the son of Maximian, while Severus was assassinated. The following year, Maximian came out of retirement to take up office again.

Galerius arranged a conference at Carnuntum (308). That gave rise to the constitution of the Second Tetrarchy, which left the East to Galerius and Maximinus Daia, and entrusted the West to Constantine and a newcomer, Licinius. Maximian and Maxentius, however, maintained their claims, and Domitius Alexander declared his own in Africa. Thus there were then seven emperors. The inevitable consequence of the Tetrarchy, this Heptarchy closely resembled anarchy.

Murder clarified the issue of succession. Maximian was the first to die, in 310, followed by Domitius Alexander and Galerius. In 312, in the battle of the Milvian Bridge (today’s Ponte Molle on the Tiber), but in fact at Saxa Rubra, Constantine defeated Maxentius, and a victory at Adrianople in 313 gave Licinius success over Daia. In 324 Constantine defeated Licinius in the battle of Adrianople, and re-established the rule of one.” (Le Glay:2009:478-79)

In Byzantium Constantine decides to build his new capital of the Roman Empire, and this he renames Constantinople, not Christendom where he builds a massive statue of himself, not Christ, to be housed in a Christian church where the classical world’s art treasures are housed. However as a power-broker he knows no-one in the East and has no contacts or political command in the Republic, and so he uses Christianity as another way of taking power by reciprocating to Christians of power as a technique of stabilising his own power structures.

Once these power structures are in place he attempts to bring the Roman senators over to his new capital in the East but they refuse. They have seen three other ‘new Capitals’ arise and fall from such new emperors and are not at all convinced that this one will last any longer than these did. But regardless of the powerless Roman Senate the power of Rome is unmistakably moving to the East.

“The vast majority of his subjects are not Christians, he cannot force them to become one so he uses benefits. Pagans are not persecuted but Christian communities are rewarded and individual Christians are given prominent positions in the hierarchy. “It was a potent force for unification…placing himself alongside the Son of God”-Dr Chris Kelly- university of Cambridge.

‘Constantine didn’t think of Christianity as being wishy washy turn the other cheek. He turned to Christianity to consolidate his power by making it the heart of the empire. Constantine made Sunday, the day of the Sun, a holiday but at court maintained a Christian image. No-one really knows if he was Christian or not, but he use to harangue his senate with hell threats if they didn’t obey him, as this was more powerful than telling them that he would punish them’. I Caesar- The men who ruled the Roman Empire. BBC Documentaries

“From these vague and indefinite expressions of piety, three suppositions may be deduced, of a different, but not of an incompatible nature. The mind of Constantine might fluctuate between the Pagan and the Christian religions. According to the loose and complying notions of Polytheism, he might acknowledge the God of the Christians as one of the many deities who composed the hierarchy of heaven. Or perhaps he might embrace the philosophic and pleasing idea that, notwithstanding the variety of names, of rites, and of opinions, all the sects and all the nations of mankind are united in the worship of the common Father and Creator of the universe.

But the counsels of princes are more frequently influenced by views of temporal advantage than by considerations of abstract and speculative truth. The partial and increasing favour of Constantine may naturally be referred to the esteem which he entertained for the moral character of the Christians; and to a persuasion that the propagation of the gospel would inculcate the practice of private and public virtue. Whatever latitude an absolute monarch may assume in his own conduct, whatever indulgence he may claim for his own passions, it is undoubtedly his interest that all his subjects should respect the natural and civil obligations of society. But the operation of the wisest laws is imperfect and precarious. They seldom inspire virtue, they cannot always restrain vice. Their power is insufficient to prohibit all that they condemn, nor can they always punish the actions which they prohibit. The legislators of antiquity had summoned to their aid the powers of education and of opinion. But every principle which had once maintained the vigour and purity of Rome and Sparta was long since extinguished in a declining and despotic empire. Philosophy still exercised her temperate sway over the human mind, but the cause of virtue derived very feeble support from the influence of the Pagan superstition. Under these discouraging circumstances, a prudent magistrate might observe with pleasure the progress of a religion, which diffused among the people a pure, benevolent, and universal system of ethics, adapted to every duty and every condition of life; recommended as the will and reason of the Supreme Deity, and enforced by the sanction of eternal rewards or punishments. The experience of Greek and Roman history could not inform the world how far the system of national manners might be reformed and improved by the precepts of a divine revelation; and Constantine might listen with some confidence to the flattering, and indeed reasonable, assurance of Lactantius. The eloquent apologist seemed firmly to expect, and almost ventured to promise, that the establishment of Christianity would restore the innocence and felicity of the primitive age; that the worship of the true God would extinguish war and dissension among those who mutually considered themselves as the children of a common parent; that every impure desire, every angry or selfish passion, would be restrained by the knowledge of the gospel; and that the magistrates might sheathe the sword of justice among a people who would be universally actuated by the sentiments of truth and piety, of equity and moderation, of harmony and universal love.

The passive and unresisting obedience which bows under the yoke of authority, or even of oppression, must have appeared, in the eyes of an absolute monarch, the most conspicuous and useful of the evangelic virtues. The primitive Christians derived the institution of civil government, not from the consent of the people, but from the decrees of heaven. The reigning emperor, though he had usurped the sceptre by treason and murder, immediately assumed the sacred character of vice-regent of the Deity. To the Deity alone he was accountable for the abuse of his power; and his subjects were indissolubly bound, by their oath of fidelity, to a tyrant who had violated every law of nature and society. The humble Christians were sent into the world as sheep among wolves; and, since they were not permitted to employ force, even in the defence of their religion, they should be still more criminal if they were tempted to shed the blood of their fellow-citizens in disputing the vain privileges, or the sordid possessions, of this transitory life….

They might add that the throne of the emperors would be established on a fixed and permanent basis, if all their subjects, embracing the Christian doctrine, should learn to suffer and to obey.” (Gibbon:1998:371-3)

04: The founding of Constantinople

‘330 AD 11 May at the New Hippodrome at not Byzantine but Constantinople. It was a dedication ceremony to a new god- Christ. statues of Deified emperors were paraded around the Hippodrome. Why did he switch from Rome, because ‘he was a pragmatic power broker’ and thriving heart of Rome was now in the East whilst its chief enemy Persia was also there. So straddling Europe and Asia was perfect place to rule both. But that wasn’t the only reason. Constantines dramatic conversion to Christianity gave him the chance to make a Christian city outside of Rome.’ Byzantium: A Tale of Three Cities- Simon Sebag Montefiore: BBC One

The emperor gave his name to the new city he founded in the East, Constantinople. The decision had been made in 324, and the inauguration took place on May 11, 330. The new town, covering the former Byzantium on the shores of the Bosporus strait, was laid out in a purposeful imitation of Rome: it lay on seven hills, was divided into 14 regions, and possessed a forum, a capitol, and a Senate….there should be no misconception over the significance of the foundation of Constantinople. It was not an act of public benefaction, or an aesthetic choice, but the result of a careful consideration of a profound change: the Empire’s centre of gravity had shifted eastward in every area: politics, economy, religion, culture.” (Le Glay:2009:480-81)

Acting in the manner of the Imperial Cult that we have studied previously Constantine, in like manner as to Alexander the Great and his father Philip of Macedon, now starts to become Persian in his dress and temperament, donning purple crowns, surrounding his court with eunuchs, and regalia to praise himself and advertise his authority. Through these techniques of power, ‘Emperors have become elevated above their subjects, by this increasing mass of courtiers, who are there to keep this distance’. Upon his death Constantine will be buried In Nicomedia, clothed in opulent silks that gleamed white, refusing to ever be clothed in purple again, he is baptised on his death bed. Buried with 12 others representing Christ’s apostles:

“The Imperial city of Constantinople was, in some measure, raised at the expense, and was adorned with the spoils, of the opulent temples of Greece and Asia; the sacred property was confiscated; the statues of gods and heroes were transported, with rude familiarity, among a people who considered them as objects, not of adoration, but of curiosity: the gold and silver were restored to circulation; and the magistrates, the bishops, and the eunuchs, improved the fortunate occasion of gratifying at once their zeal, their avarice, and their resentment. But these depredations were confined to a small part of the Roman world; and the provinces had been long since accustomed to endure the same sacrilegious rapine, from the tyranny of princes and proconsuls, who could not be suspected of any design to subvert the established religion.” (Gibbon:1998:446)

“What were his motives? In the 4th century the greatest Christian monument built by Constantine was a mausoleum and a church. Around the tomb were 12 niches for the apostles tombs and bang in the middle was a thirteenth tomb- his own sarcophagus… There is a theory that he was trying to set himself up to be Christ himself, and his own son had him moved from this central position in order to stop the protests to this. Controversial but may be true.” Byzantium: A Tale of Three Cities- Simon Sebag Montefiore: BBC One

“Jones’s views on this subject are of the greatest interest. The Later Roman Empire, in his opinion, was marked by an exceptional degree of social mobility. In the Eastern Empire, this social mobility favoured the growth of a loyal administrative class; while, in the West, this mobility was brought to a halt by the power of the senatorial aristocracy, who, by the middle of the fifth century, enjoyed a monopoly of high office. The amazing spread of Christianity after the conversion of Constantine illustrates this clearly: for this, ‘the most audacious act ever committed by an autocrat in disregard and defiance of the vast majority of his subjects’, is now seen to coincide with a regrouping of the Roman social hierarchy around the Imperial court.

Continued study of the ‘speed’ and the ‘area’ of such mobility is not only vital to our understanding of the general ‘sensitivity’ of the upper classes of the Empire to the initiative of the Emperor: it affects our view of the religion and culture of the age; it can be invoked to explain both the ‘classicizing’ of Christianity, and the corresponding cheapening of classical culture as a mark of status hastily acquired by the new professional classes.” (Brown:1972:63-4)

In the description of Constantine’s burial we can see that conflicting natures of Constantines roles in life, was he a god or was he the Son of God or was he not a god but a conduit of God? Through the tradition of the pagan imperial cult as clearly exemplified in the purple robes he donned in life to the white robes that usurped these robes in death to reflect those of Christ in the tomb, we can see this conflict. As to the twelve apostles and the twelve gods of the zodiac that surrounded Philip II of Macedon in a pagan theatre, back to the zodiac of Noah and Ziusudra in the oldest story every recorded- the Epic of Gilgamesh, we merely return to the previous chapters point about the Nature of the Logos and of this paradox that Constantine typified in every aspect of his being, or at least ‘act’.

At Rome Constantine has his eldest son Crispus, and his wife Fausta secretly executed as they are challenging his rule. He also instigates laws on adultery and on marriage because Crispus and Fausta had been having an affair.

‘In the Western Empire the Barbarians are becoming organised. Aged 58 Constantine takes army across the Danube and defeats Goths and Dalmatians. Those who surrender on his terms are enrolled in Roman way of life, given land, and he takes the sons of these new rulers into the army- in a policy of assimilation. This was a very popular policy because people wanted to become assimilated. In fact more people than Rome could take into its circle. They would actually hang around the gates of Rome awaiting assimilation. This meant more soldiers, and more administrators, etc, to be paid as they become a part of Rome, and this changed the balance of labourers to the unproductive labour of administrators and soldiers. ‘So the system he creates has within itself the seeds of its own destruction.’ I Caesar- The men who ruled the Roman Empire. BBC Documentaries

His struggle now is to unify both a Roman and Christian empire. In just 70 years Rome itself would be sacked by the Goths- a people who are Christians but not Romans.

Now that we have seen the life of Constantine I wish to show the way that the Roman classical concept of the world met with the new Christian world once Christianity came to power from its heretical history in Roman thrownness of their world? How did the pagan Senate of Rome react to the Christians who were favoured by Constantine? How did the Church see itself now that it had the stick-wielding authority of arms by which to assert itself in the worlding of the World?

To do this it is easiest to look at the life of Augustine and the formation of the Church itself:

05: Augustine sires a Violent Church from a Violent Empire

“The historian of Donatism must start, not with the social history of North Africa, but with the implications of two distinct views of the role of a religious group in society: the one, that the group exists above all to defend its identity- to preserve a divinely-given law, Machabaeico more; the other, that it may dominate, ‘baptize’ and absorb, by constraint if need be, the society in which it is placed. The controversy of the age of Augustine decided in which of these two forms Christianity would come to predominate in Western Europe: ‘if it arose in Syria, it was in and through Africa that it became the religion for the world’ (Mommsen, The Provinces of the Roman Empire, II, 343).” (Brown:1972:338)

“ ‘Classical’ political theory, from the seventeenth century onwards, was based upon a Rational Myth of the State. By myth I mean the habit of extrapolating certain features of experience, isolating them, in abstraction or by imagining an original state in which only those elements were operative, and using the pellucid myth thus created as a means of explaining what should happen today. The tendency, therefore, was to extrapolate a rational man; to imagine how reason, and a necessity assessed by reason, would lead him to found a state; and to derive from this ‘mythical’ rational act of choice, a valid, rational reason for obeying, or reforming, the state as it now is. By contrast, medieval thought, like modern thought, is neither concerned with a myth of the state, nor to base the fact of political obedience upon this myth. Both regard it as impossible to extrapolate and isolate man in such a way. Political society exists concretely: whether because of God, or history, does not matter; it is there. Above all, the link between the individual and the state cannot be limited to a rational obligation. As it exists, in fact, it is mysterious. We are linked to political society by something that somehow escapes our immediate consciousness: by a whole tangled skein of pressures and motives, some rational, many more not so. It is the nature of this tangled skein that perplexed medieval, as it now perplexes modern, thinkers. A man just finds himself in a situation in which men, for all the world like himself, are in a position to kill him, or to order him to kill others. Should this be so? Is it worth it? Is it right? In what circumstances may it be resisted? By what means may it be controlled?” (Brown:1972:26-7)

“It is from this direction that we must approach Augustine’s contribution to the Christian doctrine of passive obedience. He is a man for whom the delusion of self-determination appears as far more dangerous than any tyranny: ‘Hands off yourself’ he says. ‘Try to build up yourself, and you build a ruin.’ It is important to note the way in which this obedience is seen to rest on the individual.” (Brown:1972:30)

“A man is humble before his rulers because he is humble before God. His political obedience is a symptom of his willingness to accept all processes and forces beyond his immediate control and understanding. Thus, he can even accept the exercise of power by wicked men.” (Brown:1972:30)

“An acute sense of the spiritual dangers of excessive claims to self-determination lies at the root of Augustine’s doctrine of passive obedience: and it forms a somewhat oppressive feature of his political activities as a bishop. But it is only the negative facet of a positive doctrine. It is the positive doctrine of ordo– of the divine order of the universe- that predominates in the City of God. Man cannot claim complete self-determination because of his place in the divine order of things: in that order, he is tuned to one pitch and to one pitch only.” (Brown:1972:31-2)

“think of highwaymen, tortured because they will not reveal the names of their accomplices. ‘They could not have done this without a great capacity for love’. Augustine is acutely aware of the juxtaposition of these two elements. On the one hand, there is the self-evidence of a divine order of supreme beauty, to be contemplated in nature and in the absolute certainties of the laws of thought: on the other hand, the fact that, in this beautiful universe, the human soul tends to disperse itself in a baffling multiplicity of intense but partial loves. Such human loves only hint at a lost harmony; and it is the re-establishment of this harmony, by finding man’s proper place and rhythm, that constitutes, for Augustine, the sum total of Christian behaviour.

Augustine’s moral thought, therefore, is devoted to the re-establishment of a lost harmony. Because of this, human action is judged in terms of its relations. A good action is one that is undertaken in the light of a relation to a wider framework: the word referre, ‘to refer’, or ‘relate’, is central to Augustine’s discussion of human activity; and for Augustine, of course, this human activity, of whatever kind, can only reach fulfilment when it can take its place in a harmonious whole, where everything is in relation to God.” (Brown:1972:32-33)

“The Christian subjects to whom he preached, and the Christian officials to whom he wrote advice, were not, for Augustine, ‘natural political animals’; they were men faced with a whole range of aims and objects of love, of which those created by living in political society were only some among many others. They reacted to these aims not because they lived in a particular type of state, but because they were particular types of men. Put briefly, Augustine’s political theory is based upon the assumption that political activity is merely symptomatic: it is merely one way in which men express orientations that lie far deeper in themselves. The Christian obeys the state because he is the sort of man who would not set himself up against the hidden ways of God, either in politics or in personal distress. The Christian ruler rules as he does because he is humble before God, the source of all benefits.

These remarks on the duties of the subject and the quality of the Christian ruler were welcome at the time. They showed that Christian ethics could absorb political life at a moment when pagans had begun to fear that Christianity had proved itself incompatible with Roman statecraft. They influenced the middle ages profoundly, because they provided a totally Christian criterion of political action in an unquestioningly Christian society…Indeed, in Augustine’s opinion, one swallow did not make a summer. When he wrote the City of God, he was convinced of the collective damnation of the human race, with the exception of a small few, predestined to be ‘snatched’ from that ‘damned lump’. The symptoms, therefore, which tend to predominate in his description of human political activity can only be thought of as symptoms of a disease. The roots of this disease go very deep indeed: it is first diagnosed, not even in Adam, but in the Fall of the Angels. The most blatant symptom of this fall is the inversion of the harmonious order established by God.” (Brown:1972:35)

![]() Writer’s Voice: For scientologists it may be nice to know that this mad-house that by inter-galactic law no alien is allowed to land on Earth in case of infection, that this is not news to Christianity, despite the fact that scientologists are told that Christianity is a part of the brain-washing. It is not Christianity but ignorance of Christianity (admittedly the majority of which comes from Christians themselves) that is the brain-washing- As I am sure scientologists feel about their religion and how it is portrayed to others.

Writer’s Voice: For scientologists it may be nice to know that this mad-house that by inter-galactic law no alien is allowed to land on Earth in case of infection, that this is not news to Christianity, despite the fact that scientologists are told that Christianity is a part of the brain-washing. It is not Christianity but ignorance of Christianity (admittedly the majority of which comes from Christians themselves) that is the brain-washing- As I am sure scientologists feel about their religion and how it is portrayed to others.

“Thus, first the Devil, then Adam, chose to live on their own resources; they preferred their own fortitude, their own created strength, to dependence upon the strength of God. For this reason, the deranged relationships between fallen angels and men show themselves in a constant effort to assert their incomplete power by subjecting others to their will. This is the libido dominandi, the lust to dominate, that was once mentioned in passing by Sallust, as an un-Roman vice, typical of aggressive states, such as Assyria, Babylon and Macedon. It was fastened upon by Augustine as the universal symptom par excellence of all forms of deranged relationships, among demons as among men. Seen in this bleak light, the obvious fact of domination, as a feature of political society, could make the world of states appear as a vast mental hospital, ranging from the unhealthy self-control of the early Romans to the folie de grandeur of a Babylonian tyrant. This was a bitter pill, which many lay rulers were forced to swallow in later ages. But, as always with Augustine, the outward expression of this ‘lust’ in the form of organized states is merely a symptom…A libido, for Augustine, was a desire that had somehow got out of control: the real problem, therefore, was why it had got out of control, what deeper dislocation this lack of moderation reflected…

We emphasize this aspect of Augustine’s thought because we tend to treat the state in isolation. But this is something which Augustine never did, at any time. The object of his contemplation, the aspect of human activity that he sought to make intelligible and meaningful, is not the state: it is something far, far wider. For him, it is the saeculum. And we should translate this vital word, not by ‘the world’, so much as by ‘existence’- the sum total of human existence as we experience it in the present, as we know it has been since the fall of Adam, and as we know it will continue until the Last Judgement.

For Augustine, this saeculum is a profoundly sinister thing. It is a penal existence, marked by the extremes of misery and suffering, by suicide, madness, by ‘more diseases than any book of medicine can include.’, and by the inexplicable torments of small children.” (Brown:1972:36-7)

![]() Writer’s Voice: For scientologists it may be nice to know that this mad-house that by inter-galactic law no alien is allowed to land on Earth in case of infection, that this is not news to Christianity, despite the fact that scientologists are told that Christianity is a part of the brain-washing. It is not Christianity but ignorance of Christianity (admittedly the majority of which comes from Christians themselves) that is the brain-washing- As I am sure scientologists feel about their religion and how it is portrayed to others.

Writer’s Voice: For scientologists it may be nice to know that this mad-house that by inter-galactic law no alien is allowed to land on Earth in case of infection, that this is not news to Christianity, despite the fact that scientologists are told that Christianity is a part of the brain-washing. It is not Christianity but ignorance of Christianity (admittedly the majority of which comes from Christians themselves) that is the brain-washing- As I am sure scientologists feel about their religion and how it is portrayed to others.

The out of control is the lack of the egoic desire that we have seen drive this desire to culture and war.

“The most obvious feature of man’s life in this saeculum is that it is doomed to remain incomplete. No human potentiality can ever reach its fulfilment in it; no human tension can ever be fully resolved. The fulfilment of the human personality lies beyond it; it is infinitely postponed to the end of time, to the Last Day and the glorious resurrection. Whoever thinks otherwise, says Augustine: ‘understands neither what he seeks, nor what he is who seeks it.’

For Augustine, human perfection demands so much, just because human experience covers so very wide an area, a far wider area than in most ethical thinkers of the ancient world. It includes the physical body: this dying, unruly thing cannot be rejected, it must be brought into its proper place and so renewed. It includes the whole intense world of personal relationships: it can only be realized, therefore in a life of fellowship, in a vita socialis sanctorum. It is inconceivable that such claims can be met in this world; only a morally obtuse man, or a doctrinaire, could so limit the area of human experience as to pretend that its fulfilment was possible in this life. Thus, in opening his Nineteenth Book of the City of God by enumerating and rejecting the 288 possible ethical theories known to Marcus Varro as ‘all those theories by which men have tried hard to build up happiness for themselves actually within the misery of this life.’, Augustine marks the end of classical thought. For an ancient Greek, ethics had consisted of telling a man, not what he ought to do, but what he could do, and hence, what he could achieve. Augustine, in the City of God, told him for what he must live in hope, in faith, in an ardent yearning for a country that is always distant, but made ever-present by the quality of his love, that ‘groans’ for it, Augustine could well be called the first Romantic.” (Brown:1972:38-9)

![]() Writer’s Voice: So for Augustine, being-in-Being, the state that we saw exist for tens of thousands of years is impossible in this world, but that it is only fellowship that can bring human perfection. As we have seen he is therefore right and wrong as it is fellowship that was the point of alimental communion between human-beings and Being in their relationship to God as Wakan- and were met in this world. Unfortunately Catholicism is destined to create autodynamism to defeat the heterodynamism that it encounters in the world and not homodynamism. I do not think that this is romantic but tragic. My theory is romantic when seen through the lense of ignorance (common sense of human-being today) that we have now polished and removed, augustine’s is tragic because it states that life is pointless once you have taken the sacraments of the church and then become politically obedient to evil rulers causing suffering and scapegoats all around you in this homodynamic wakan spirit, the Greeks is tragic because it does the same thing- not for its own salvation, but for its own holiness, or wholeness, which results always in the nemesis of lack ever-increasing.

Writer’s Voice: So for Augustine, being-in-Being, the state that we saw exist for tens of thousands of years is impossible in this world, but that it is only fellowship that can bring human perfection. As we have seen he is therefore right and wrong as it is fellowship that was the point of alimental communion between human-beings and Being in their relationship to God as Wakan- and were met in this world. Unfortunately Catholicism is destined to create autodynamism to defeat the heterodynamism that it encounters in the world and not homodynamism. I do not think that this is romantic but tragic. My theory is romantic when seen through the lense of ignorance (common sense of human-being today) that we have now polished and removed, augustine’s is tragic because it states that life is pointless once you have taken the sacraments of the church and then become politically obedient to evil rulers causing suffering and scapegoats all around you in this homodynamic wakan spirit, the Greeks is tragic because it does the same thing- not for its own salvation, but for its own holiness, or wholeness, which results always in the nemesis of lack ever-increasing.

“Augustine’s attempts deliberately and persistently to see in human society the expression of the most basic and fundamental human needs….

He finds this fundamental need in the human desire for peace…This pax, for Augustine, means far more than tranquillity, unity and order. These things are only preconditions for its attainment. For Augustine, the obverse of peace is tension- the unresolved tension between body and soul and man and man, of which this life is so full…His concern with peace as something absolutely fundamental to human happiness made him welcome any feature of organized society that might at least cancel out some of those tensions of which he was so intensely conscious.

For this reason, Augustine could accept the domination of man over man that had arisen from the Fall. This domination at least cancelled out certain tensions- although at a terrible cost, as anyone who has witnessed judicial torture and executions, would admit if he had any sense of human dignity. But at least an ordered hierarchy of established powers can canalize and hold in check the human lust for domination and vengeance. For Augustine, like Hobbes, is a man for whom a sense of violence forms the firmest boundary stone of his political thought.” (Brown:1972:40-1)

![]() Writer’s Voice: So Peace is a desire produced by war which is nothing more than desire organised, but that is okay because violence curbed- war is better than random violence- warfare. Therefore Romes Empire is better than no Empire. And a Catholic Empire will be better than no Empire.

Writer’s Voice: So Peace is a desire produced by war which is nothing more than desire organised, but that is okay because violence curbed- war is better than random violence- warfare. Therefore Romes Empire is better than no Empire. And a Catholic Empire will be better than no Empire.

“The weakness of Augustine’s position is, of course, that it implies a very static view of political society. It is quite content merely to have some of the more painful tension removed. It takes an ordered political life for granted. Such an order just happens among fallen men. Largely because he feels he can take it for granted, Augustine can dismiss it. For him, it is a ‘peace of Babylon’ that should only be ‘used’ by the citizens of the Heavenly City…. He therefore, rejects as too narrow the classical definition of the res publica: such a definition would make it appear as if political society were a mere structure designed to protect certain rights and interests. For Augustine, this misses the point. Men, because they are men, just do cohere, and work out some form of normative agreement- an ordinata concordia. What cannot be taken for granted is the quality of this ordered life; and, for Augustine, this means the quality of the motives and aims of its individual members…. ‘it is a better or a worse people as it is united in loving higher or lower things.’

…It hits upon a fundamental motive: dilectio, which, for Augustine, stands for the orientation of the whole personality, its deepest wishes and its basic capacity to love, and so it is far from being limited to purely rational pursuit of ends. It is dynamic; it is a criterion of quality that can change from generation to generation.” (Brown:1972:41-2)

![]() Writer’s Voice: When this love turns into self-love (being-in-itself) or familist-love (being-for-others) or political-love (being-as-subject) then it is a lower thing than being-in-Being, i.e. not fallen, whereupon the relationship to beings and Being are one.

Writer’s Voice: When this love turns into self-love (being-in-itself) or familist-love (being-for-others) or political-love (being-as-subject) then it is a lower thing than being-in-Being, i.e. not fallen, whereupon the relationship to beings and Being are one.

“Today, perhaps, we can appreciate the importance of this shift of emphasis. Previously, it could be assumed that political theory was a matter of structure, in an almost mechanical sense. In discussing this structure, we had tended to analyse it into its component parts, and, hence, to isolate the individual on the one hand, and the state, on the other, as the only two parts whose relations are relevant to thought on political society. In fact, this isolation is a deliberately self-limiting myth. So much of our modern study in sociology and social psychology has shown the degree to which political obedience is, in fact, secured, and political society coheres by the mediation of a third party, of a whole half-hidden world of irrational, semi-conscious and conscious elements, that can include factors as diverse as childhood attitudes to authority, crystallized around abiding inner figures, half-sensed images of security, of greatness, of the good life, and, on the conscious plane, the acceptance of certain values. These make up an orientation analogous to Augustine’s dilectio.

…Viewed in such a way, the state becomes a symbol: it is one of the many moulds through which men might be led to express needs and orientations that lie deep in themselves; and the expression of these needs through an organized community provides a far more tenacious bond of obligation than the purely rational agreements of a social contract.” (Brown:1972:43)

“In later centuries, in a society where the external role of the Church will become more explicit, Augustine’s subtle, dynamic doctrine in which values form a field of forces, linking what men really want in their hearts with what they want from a state, will settle down as a static hierarchy of duties….

…We are left with a dichotomy: an acute awareness of the actual condition of man in this saeculum; and a yearning for a City far beyond it. Augustine never overcame this dichotomy.” (Brown:1972:45)

![]() Writer’s Voice: The desires of the state are by its pyramid nature and method of cohesion- money, esteem and power- obliged to create desire in the individual for its own self, and not for the higher Being, by which it derives its authority. In other words, War is innate within a pyramid civilization and hence peace is a desire that is created in order to justify war in order to obtain it. This is Augustine’s naivety about the body politic and the type of animal (spirit) that it is by its very nature. Its dilectio is not Augustine’s dilectio- It is not love but self-love by which the fallen act. To dismiss this is to not understand institutional fundamentals, and hence to see violence as a boundary stone and not a central anchor point of survival of the fittest (the self-love perspective) but as the means to embody harmony (the universal-love perspective)- a boundary stone.

Writer’s Voice: The desires of the state are by its pyramid nature and method of cohesion- money, esteem and power- obliged to create desire in the individual for its own self, and not for the higher Being, by which it derives its authority. In other words, War is innate within a pyramid civilization and hence peace is a desire that is created in order to justify war in order to obtain it. This is Augustine’s naivety about the body politic and the type of animal (spirit) that it is by its very nature. Its dilectio is not Augustine’s dilectio- It is not love but self-love by which the fallen act. To dismiss this is to not understand institutional fundamentals, and hence to see violence as a boundary stone and not a central anchor point of survival of the fittest (the self-love perspective) but as the means to embody harmony (the universal-love perspective)- a boundary stone.

By seeing it as a boundary stone however, Augustine was able to bring violence easily into the arms of the Church, by which it could ‘hold’ its flock- remember that religion means ‘to bind’. It is allegorically meant to mean ‘to bind’ as in the Nature of the Vine of Christ or the Ivy of Dionysus that climbs ever higher towards the light together in harmony, as we climb the tree of knowledge (ka-ba-lah), but it comes to mean under Augustine ‘to bind’ to ‘The Church’, ‘the Catholic Church-in-itself’. This meant that the Universe that contained pagans could not be housed within a universe (Catholic) that did not worship the Logos as Christ The son of God, because the boundary had been laid down by his theology and it’s first stone cast across this liminal invisible circle was, you guessed it, violence in the name of peace, for our sakes, in order to attain political obedience without question even to evil rulers. Augustine’s nick-name was ‘The Prince of Persecutors’:

“Above all, they had suppressed pagans and heretics. Augustine was deeply involved in this last change. He is the only bishop in the Early Church whom we can actually see evolving, within ten years, towards an unambiguous belief that Christian emperors could protect the Church by suppressing its rivals. He is the only writer who wrote at length in defence of religious coercion; and he did this with such cogency and frequency that he had been called le prince et patriarche des persécuteurs.” (Brown:1972:44)

![]() Writer’s Voice: What therefore were the repercussions of Augustine’s thoughts to how the Church subsequently behaved, and how did this contribute to the fall of Rome itself through the increase of violence in the Roman Empire?

Writer’s Voice: What therefore were the repercussions of Augustine’s thoughts to how the Church subsequently behaved, and how did this contribute to the fall of Rome itself through the increase of violence in the Roman Empire?

“In the West, Christian opinion, in the late fourth century, was prepared neither to respect those who kept the barbarian outside the Empire, nor to tolerate and absorb the barbarian, once inside. Western Christianity was not ‘pacifist’. Rather, it became respectable through crystallizing the latent anti-militarism of the civilian population: this is already evident in the ‘senatorial’ apologetic of Lactantius. Unlike the medieval Byzantine Empire, Western society of the early Middle Ages failed notably to find an honourable place for the Roman soldier.

At one and the same time, to be respectable involved keeping the barbarian at arm’s length. Ambrose, for instance, will expect his readers to assume that the barbarian must be a heretic, and the heretic a barbarian….

One cannot resist the impression that it was the new intolerance of the ‘respectable’ Catholicism of the later fourth century which kept the barbarian kingdoms ‘barbaric’: it forced the Visigothic; Vandal and Ostrogothic ruling classes in on themselves; it fostered their Arianism; it checked their ‘detribalization’, and so it ringed the Mediterranean of the late fifth and sixth centuries with precarious, encapsulated minorities, the regna gentium.” (Brown:1972:53-4)

“the worst catastrophes of the Roman Empire were precipitated by the belief that the primitive methods applied to the inhabitants of the Empire by its bureaucracy- the eternal short-cut of the coercion of social groups (II,1051)- could be successfully extended to embrace the transfer of barbarian populations.” (Brown:1972:59)

“Far from making the processes of Romanization more flexible, the Christian church made them more rigid by equating civilization with orthodoxy. The inhabitants of the Val di Non, for instance, who had become civilized in an old-fashioned way, would be dismissed by the bishop of Trent as a natio Barbara: for though Roman, they had remained pagan (Vigilius of Trent, Epistula I, I P.L. 13,550 D).

This greater inflexibility played a disastrous role in the relations of the Empire with the barbarians. In the fourth century, the barbarian chieftain could be accepted without comment on becoming Romanized….The policy by which the Emperor Theodosius hoped to save the Empire from the Gothic menace assumed that the bridge between the barbarian world and the Roman was still open: the rank and file of the tribesmen would be deprived of their leaders and would be controlled by a Gothic aristocracy, skilfully seduced by the offer of full participation in the benefits of Roman civilized life….But just such a policy was being sabotaged by the intolerance of the Catholic bishops patronized by the same Emperor: for a bishop, orthodoxy was the only bridge over which a barbarian could enter civilization; and in the eyes of John Chrysostom, a Goth who was fully identified with the Roman order by pagan standards but who had remained an Arian, might just as well have stayed in his skins, across the Danube.” (Brown:1972:90-91)

“But, given the intellectual equipment which Dr Frend describes in the Greek apologists- a robust faith that, in a stable and civilized community, the tensions between religious belief and secular peace can be reconciled- it is not surprising that the most lasting legacy of Byzantine ecclesiastical statecraft should have been the idea of the Peace of the Church…

In Western Europe, the propounders of the idea of the Church, and, consequently, the idea of the Christianized society, were less certain that such tensions could be resolved, and, for that reason, were more aggressive: a church that always thought of itself as a separate elite could either be persecuted or dominant’ and the world outside it, regarded either as actively hostile or as inferior, as a backward colony to be ruled firmly, with a heavy, guilt-laden paternalism. Augustine provides the alchemy that turned the persecuted elite of Cyprian into the persecuting elite of later times. In the West, therefore, the Christian society will always be pushing against its frontiers: a distinctive idea of the Church, held in varying degrees of crudity, blesses the impingement of Western Europe on the outside world in the Crusade, in the Reconquista, in the constant pressure against the pagans in Eastern Europe and along the shores of the Baltic…Not surprisingly, the catechism which Augustine wrote to aid a Carthaginian priest in absorbing demoralized pagans after the destruction of their great temples in 399- a catechism in which the ‘gathered’ church of Cyprian has been subtly transposed into the triumphant elite of the age of Theodosius the Great- forms the basis of the first catechism published by the Spaniards in the New World.” (Brown:1972:92-3)

![]() Writer’s Voice: we shall see this catechism’s dynamic repercussions in the New World where people of Wakan are currently living, and will be until 1492, later on.

Writer’s Voice: we shall see this catechism’s dynamic repercussions in the New World where people of Wakan are currently living, and will be until 1492, later on.

06: Mani and his Daemon – Remember the Fate of Socrates and his Daemon or Christ and his Angels?

“The condemnation of the wisest and most virtuous of the Pagans, on account of their ignorance or disbelief of the divine truth, seems to offend the reason and the humanity of the present age. But the primitive church, whose faith was of a much firmer consistence, delivered over, without hesitation, to eternal torture the far greater part of the human species. A charitable hope might perhaps be indulged in favour of Socrates, or some other sages of antiquity, who had consulted the light of reason before that of the gospel had arisen. But it was unanimously affirmed that those who, since the birth or the death of Christ, had obstinately persisted in the worship of the daemons, neither deserved, nor could expect, a pardon from the irritated justice of the Deity. These rigid sentiments, which had been unknown to the ancient world, appear to have infused a spirit of bitterness into a system of love and harmony.” (Gibbon:1998:260-1)

“For Cumont, Manichaeism was the direct successor of Mithraism in the Western world.

The general reassessment of the nature of Manichaeism, followed by the discovery of the Coptic Manichaean documents in the Fayyūm in Egypt has made in increasingly difficult to represent Manicheanism as a development of Iranian religion. The Manichees entered the Roman Empire, not as a final version of the Mages Hellenisés, but at the behest of a man who claimed to be an ‘Apostle of Jesus Christ’: the intended to supersede Christianity, not to spread the scaevas leges Persarum. Diocletian had made the mistake, pardonable in a Roman if not in a modern historian of Near Eastern culture, of treating Persian-controlled Mesopotamia tout court as ‘Persia’.

Mani belongs where he said he belonged, to the ‘land of Babylon’…He looks back to the Gnostic Christianity of Osrhoene: his dialogue is with Marcion and Bardasian of Edessa; Zoroaster is a distant figure to him.” (Brown:1972:96-7)

“We know three of the most important things about Mani. He was a missionary: not for nothing did he borrow the Pauline title of ‘Apostle of Jesus Christ’ for his letters. He was deeply preoccupied with the problem of national boundaries. He believed that he had founded a universal religion: unlike Christianity and Zoroastrianism, he would be able to spread the ‘hope of life’ in East and West alike. East had been East, and West had been West; and only in Mani had the twain met. He was a man with a daemon. From the age of twelve, he had acted on the prompting of his ‘Twin Spirit’. The final distillation of religious truth- the Holy Ghost that had been promised three centuries before Christ- had descended in him. With this belief he sent his disciples to East and West, and he himself lived a life of great missionary journeys.

Now, the interest of Mani’s journeys is that, radiating from Mesopotamia, they usually strike inland, into the traditional world of the Iranian plateau: only once did he hover on the frontiers of the Roman Empire. Socially, he seems to have impinged intimately on the Iranian governing class: he acted on the fringes of the Sassanian royal family; he converted client kings, and female members of the Iranian aristocracy. Thus for thirty years Mani had preached, performed exorcisms, conjured visions near the heart of traditional Persian society, which knew him as ‘the doctor from the land of Babylon’. When he was executed, in 276, it was at the instigation of the Zoroastrian clergy, led by the modedhan modedh, Karter, on the charge of having provoked apostasies from Zoroastrianism. Mani was not the last religious leader in the Sassanian Empire to suffer for claiming that his was a universal faith, and that the ‘Good Religion’ of Zoroaster was both demonic and parochial.” (Brown:1972:99-100)

“First, the Manichean religion as based on a rigid distinction between the perfect, the Elect (men and women), and the rank-and-file, the Hearers. The sancta ecclesia of Mani was limited to the Elect. The Elect secured the salvation of the Hearers, by forgiving their sins and by purging their souls through entirely vicarious rituals. The Hearers sheltered and fed the Elect. Manichaeism, therefore, was a group with an unmistakable inner core: the Elect were vagrant, studiously ill-kempt, they carried exotic books, they were committed to elaborate liturgies and fenced in with drastic taboos. The Hearers, by contrast, were indistinguishable from their environment. The Manichaeism of the Hearers- of the ‘Fellow-Travellers’. Augustine and his friends were only Hearers….

A religion that has to shelter behind patrons and half-adepts is an interesting phenomenon. Strange alliances could occur. Symmachus, the pagan, will choose Augustine, the Manichean ‘Hearer’ for the chair of rhetoric in Milan at the behest of the Manichees.” (Brown:1972:108-9)

“By the end of the fourth century, therefore, Manichaeism was already shorn of an intelligentsia that had come in equal numbers from pagan and Christian families. African Manicheaism, for instance, was left with a rump of hard-core Electi, and with Hearers drawn exclusively from the fringes of the average Christian communities. The effect of persecution in the Christian Roman Empire, therefore, was to increase the ‘Christianization’ of Manichaeism, by encouraging occasional conformity and by cutting off its access to a large pool of post-pagan intellectuals.

Secondly, Manichaeism became a problem increasingly as a form of crypto-Christianity. Mani had trumped Christ: the Manichean missionary had to prove it by dogging the Christian community; and his converts would tend to remain prudently hidden under the shadow of the Catholic Church….

Hence the inquisitorial atmosphere accompanying the suppression of Manichaeism and that other form of Gnostic crypto-Christianity, Priscillianism: we hear of agents provocateurs (one zealous priest suggested adultery as a fine way of obtaining the names of heretics). The discovery of Manichees would be accompanied by lurid public ‘confession’, before the bishop, throned in the apse of the his basilica, like a Justice of the Peace….

The Christian Church appears as a labour-saving institution for the Roman state. For the problem of identifying the Manichee and of absorbing the convert devolved on the Christian clergy…

In Constantinople and the Eastern Empire, in 529, the problem of the converted Manichee was still being handled exclusively by the traditional police-mechanisms of the lay world: the bishop is peripheral. In the West, the duty of identifying and absorbing heretics had long devolved on the clergy. It is a reminder that the more, thoroughly ‘Christianized’ early Byzantine Empire will never be ‘clericized’ as rapidly as the less Christian but under-governed West.” (Brown:1972:110-12)

07: Assassination is not as powerful as Sorcery – Bureaucracy is more powerful than Sorcery – Byzantium

“This spread of education did not prevent the proliferation of superstitious beliefs, a staple of Roman civilization for centuries. Many lives were ruled by astrology, which claimed that humans were ruled by the movements of heavenly bodies. The observation of nature also encouraged a belief in magic, which claimed to be able to compel the gods through the action of spirits. Alchemy sought to transform base metals into gold. Practices of theurgy (“divine-work”) included meditation and invocation of the divine, and promised miracles and apparitions. Spell-casting tablets multiplied during the fourth century. At a mystical ceremony a magic text was inscribed on a papyrus, or a tablet of wood or metal, mostly lead, and then placed in a tomb or shaft. These tablets reveal what preoccupied people’s thoughts- love, revenge, winning on the horses, and bumper harvests.” (Le Glay:2009:525-26)

![]() Writer’s Voice: Magic becomes being-for-itself as a lens and fades from reality as an impersonal invisible force of Nature, it is now a possession to be seen from the perspective of our own nature. The very stars move in order to rule us, not to commune with us alimentally. Darpan. The alchemy of the inner world, transforming our base metals as described by Socrates into gold ones, now becomes the alchemy of the outer world, an external jihad upon Nature itself, where the value of ones life is to transform not through Promethean fire, but through physical fire, Nature itself, to our purposes, through our man-made arts. Alchemy becomes the etymology of chemistry whereas it used to be the root of religion. Progress in a tower of Babyl. What do they want from their genies- love of the self, revenge of a hated other- Peace and war, respectively, gain without effort as the aristocracy have achieved for themselves- hope, and no longer to worry about having enough to eat, as the aristocracy have achieved for themselves- fear.

Writer’s Voice: Magic becomes being-for-itself as a lens and fades from reality as an impersonal invisible force of Nature, it is now a possession to be seen from the perspective of our own nature. The very stars move in order to rule us, not to commune with us alimentally. Darpan. The alchemy of the inner world, transforming our base metals as described by Socrates into gold ones, now becomes the alchemy of the outer world, an external jihad upon Nature itself, where the value of ones life is to transform not through Promethean fire, but through physical fire, Nature itself, to our purposes, through our man-made arts. Alchemy becomes the etymology of chemistry whereas it used to be the root of religion. Progress in a tower of Babyl. What do they want from their genies- love of the self, revenge of a hated other- Peace and war, respectively, gain without effort as the aristocracy have achieved for themselves- hope, and no longer to worry about having enough to eat, as the aristocracy have achieved for themselves- fear.

“It is here that we find a situation which has been observed both to foster sorcery accusations and to offer scope for resort to sorcery. This is when two systems of power are sensed to clash within the one society. On the one hand, there is articulate power, power defined and agreed upon by everyone (and especially by its holders!): authority vested in precise persons; admiration and success gained by recognized channels. Running counter to this there may be other forms of influence less easy to pin down- inarticulate power: the disturbing intangibles of social life; the imponderable advantages of certain groups; personal skills that succeed in a way that is unacceptable or difficult to understand. Where these two systems overlap, we may expect to find the sorcerer.

In some areas, where competition is not easily resolved by normal means, we find actual resort to sorcery. Far more important, however, in a situation where articulate and inarticulate power clash, we find greater fear of sorcery, and the reprobation and hunting-down of the sorcerer. In this situation, the accuser is usually the man with the Single Image. For him, there is one, single, recognized way of making one’s way in the world. In rejecting sorcery, such a man has rejected any additional source of power. He has left the hidden potentialities of the occult untouched. He is castus. The sorcerer, by contrast, is seen as the man invested with the Double Image….

To fear and suppress the sorcerer is an extreme assertion of the Single Image. Many societies that have sorcery-beliefs do not go out of their way to iron out the sorcerer. The society, or the group within the society, that actually acts on its fear is usually the society that feels challenged, through conflict, to uphold an image of itself in which everything that happens, happens through articulate channels only- where power springs from vested authority, where admiration is gained by conforming to recognized norms of behaviour, where the gods are worshipped in public, and where wisdom is the exclusive preserve of the traditional educational machine.

The best-documented aspect of this problem is the conflict in the governing class of the Later Roman Empire between fixed vested roles, on the one hand, and the holders of ambiguous positions of personal power, on the other. This personal power was based largely on skills, such as rhetoric, which, in turn, associated the man of skill with the ill-defined, inherited prestige of the traditional aristocracies…

To take the governing class in its narrow sense and to view it from the hub onwards- that is, to analyse purges based largely on accusations of sorcery in the reigns of Constantius II, Valentinian I and Valens. The scene is usually the inner ring of the court: it is played out among officials, ex-officials, local notables. All of these men would have had personal contact with the emperor as a man, and not only as a remote figure of authority.

To rationalize such accusations as ‘smears’ is only half the truth. They certainly were not pretexts for suppressing political conspiracies. Ammianus is firm on this point: the emperor knew only too well what an assassination plot was, and suppressed it as such. Rather, these accusations indicate very faithfully a situation where organized political opposition was increasingly unthinkable: the days of a ‘senatorial opposition’, able to make itself felt by assassination, were gone forever; the civilian governing class was overtly homogeneous, and stridently loyalist. Thus, resentments and anomalous power on the edge of the court could be isolated only by the more intimate allegation- sorcery. Indeed, seen from the point of view of the emperor’s image of himself, some sorcery was even a necessity: for to survive sorcery was to prove, in a manner intelligible to all Late Roman men, that the vested power of the emperor, his fatum, was above the powers of evil directed by mere human agents. A sorcerer’s attack, indeed, in an obligatory preliminary, in biographies of the time, to demonstrating the divine power that protected the hero, whether this be the divine daemon of the pagan philosopher, Plotinus, or the guardian archangel of St. Ambrose. When we see them in this light, we can appreciate how the sorcery accusations of the fourth century mark a stage of conflict on the way to a greater definition of the secular governing class of the Eastern Empire as an aristocracy of service, formed under an emperor by divine right….

In the fourth century, the boundary between the court and the traditional aristocracy coincided, generally, with a boundary between Christianity and paganism. It is often assumed that to accuse a pagan aristocrat of sorcery was a covert form of religious persecution. (To the Christian, who took for granted that a pagan worshipped demons, it was convenient to assume that he would also manipulate them, in sorcery; and so the burning of books of magic, a traditional police action, is continued, in the Christian period, as a cover for the destruction of much of the religious literature of paganism.)” (Brown:1972:124-6)

“Throughout these accusations, therefore, we have something more than the occult measures which men in a competitive situation undeniably did take to increase their success and crush their rivals: there is an attempt to explain a theme that still puzzles the historian of the Later Empire, the je ne sais quoi of the predominance of an ill-defined aristocracy of culture and inherited prestige, constantly pressing in upon an autocracy whose servants derived their status from membership of a meticulously graded bureaucracy.

Sorcery beliefs in the Later Empire, therefore, may be used like radio-active traces in an X-ray: where these assemble, we have a hint of pockets of uncertainty and competition in a society increasingly committed to a vested hierarchy in church and state….As long as the successes of the charioteers were bound up in the public imagination with the ‘Fortune’ of the city, this usually remote and stable figure (who would be easily assimilated to the unmoved majesty of a Christian archangel) was thrown on to the ‘open market’ by the talents of a star. The charioteer himself was an undefined mediator in urban society: he was both the client of local aristocracies and the leader of organized groups of lower-class fans- and so, at times, a potential figure-head in urban rioting, that nightmare of Late Roman government. Along with athletes and actors, he belonged to the demi-monde- a very important class in the imaginations (and, one would suspect, also in the daily life) of the studiously aristocratic society of the Later Empire. Accusations of sorcery frequently take us from upper-class families into a world where charioteer and sorcerer are intimately associated.

For it is in this demi-monde, in the wide sense, that we find the professional sorcerer. The cultivated man, it was believed, drew his power from absorbing a traditional culture. His soul, in becoming transcendent through traditional disciplines, was above the material world, and so was above sorcery. He did not need the occult. We meet the sorcerer pressing upwards against this rigid barrier, as a man of uncontrolled occult ‘skill’…

It is in this demi-monde, of course, that we meet the Christian Church. Previously, the Church had been the greatest challenge from below to traditional beliefs and organization: the powers of its founders, Jesus and Peter, and of its clergy, were regularly ascribed to sorcery. Moreover, in the fourth and fifth centuries, the Church was a group which had harnessed the forces of social mobility to itself more effectively even than the teaching profession: its hierarchy was notable a carrière ouverte aux talents: and it played a decisive role in the ‘democratization’ of culture.