earthmoss

evolving our futureChapter 3 : Pandora's box and the great war of electrified mice - being-for-others

Contents / click & jump to :

- 01: Lubbock’s walk through the alleys and courtyards of beidha provides him with other new experiences.

- 02: Lets get the band back together- a limited-capital idea!

- 03: The great war of the electrified mice

- 04: Being-for-others

- 05: Such is the origin of my concrete relations with the other

- 06: Desire is a conduct of enchantment

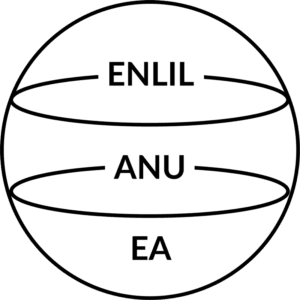

- 07: Pandora, prometheus and epimetheus

- 08: Hesiod – the homeric hymns and homerica

- 09: In order to understand this myth, we merely need to translate the names of these gods involved in the story

- 10: Hubris and nemesis and karma

- 11: The Hindu myth that will hopefully explain all of above much more clearly

- 12: The relationship between Shiva and Parvati is not based on power

![]() Note: When displayed, this icon indicates ‘Writer’s Voice’ style in text.

Note: When displayed, this icon indicates ‘Writer’s Voice’ style in text.

Introduction

Introduction

One day a snake-charmer caught a snake and charmed it with his music, to make it dance. Taking it to the market to perform for others, he received gold from those in the market-place. But whilst the man thought he had charmed the snake, he did not realise that, upon receipt of gold, the snake had charmed him.

In the last two chapters we have discovered that for the majority of human existence, we have lived in peace together, in a land of plenty, with one religion, with one God; with freedom, fraternity, and equality.

We have also seen how the perspective of this historical cave-man, and his use of language ,especially regarding being-in-Being, and dwelling, and truth itself meant different things to a being-in-Being to a being-for-itself.

In this chapter we are going to look at the being-for-itself, when it meets another being-for-itself, not, as with individual totemism and the family as met them briefly in the last chapter, where they all have the same goal, but where two egoic goals meet each other. What happens when two ‘beings-for-itself’ meet? Does one of them say, “thy will, not my will be done?”, “No, no I insist, please pretend I am not in a circle where the centre is me and not you. Go right ahead and take that which I make believe to be mine”.

In other words, we have seen mankind suddenly state the term ‘mine’, this is ‘my space’ and this is ‘my time’, due to suddenly believing in the centre as self, over Being. What then are the conditions necessary for this way of life to come into existence? Who was the first person to say, ‘that is mine’, and get away with it? As we saw previously, a being-for-itself would be either laughed at or secretly put to death, for trying to live and inculcate other members of humanity in to such a perspective of existence. Something must have shifted in order for a being-for-itself to gain through such a perspective. To receive pleasure and not pain for behaving in such a manner.

The word belief, means to be-in-lief. Lief comes from the latin word ‘libet’, meaning ‘it pleases’ and ‘libet’ itself comes from the Sanskrit word ‘lubh’, meaning ‘to desire’.

We left our families of beings-for-itself in their little circles of beliefs and farmsteads of desire, with their new leaders who emerged our of this land of plenty. Let us see what has happened to them now, and see how things are going. Is it still a land of plenty, are the leaders working for alimental communion?

“The town of Beidha is a dramatic statement of human detachment from the natural world, epitomised by the sharp angles and ordered layout of buildings, the goats within their pens, the land cleared for farming.” (Mithen:2003:72)

“The transition from small circular dwellings typical of PPNA settlements such as Jericho, Netiv Hagdud and WF16 to the relatively large, rectangular and often two-storey buildings of Beidha and other PPNB settlements documents a major social transformation. Kent Flannery from the University of Michigan has argued that this reflects a shift from a group-oriented society- in which any food surpluses are pooled and available to all- to one in which families are the key social unit. Rather than being spread out between several small circular huts, such families consolidated their presence with multiple rooms within a single building….

01: Lubbock’s walk through the alleys and courtyards of Beidha provides him with other new experiences.

In the hunter-gatherer settlements he had visited there had been few surprises- he could almost always see from one side of the village to another, most of the work occurred in the open air, and everyone seemed to know everyone else’s business. Here, as in the other Neolithic towns, turning almost every corner can lead to a surprise- unexpected clusters of people, an outdoor hearth, a tethered goat. People simply cannot know what is happening elsewhere in the town- even just a few metres away- because so much occurs behind thick walls. The number of inhabitants has become too great for people to know one another’s business and relations. There is, Lubbock senses, an atmosphere of distrust and anxiety, one brought on by the impact of town life on a mentality that had evolved for living in smaller communities.

Along with sheep, goats were the first animals to be domesticated after the dog, and completed the shift from hunting and gathering to a farming lifestyle. Precisely where, when, and why such domestication occurred is still much debated by archaeologists.

The goat is very rare in the collections of bones from Natufian and Early Neolithic villages, these being dominated by gazelle- the preferred prey ever since the LGM. So the abundance of goats found at Beidha- 80 per cent of all animals bones- suggests herding rather than hunting.

The Beidha goats were also small in size compared to known wild goats. A reduction in body-size occurs with all animals once they become domesticated- pigs are smaller than wild boar, cows smaller than wild cattle.” (Mithen:2003:76-77)

“The town of ‘Ain Ghazal made remarkable growth, reaching thirty acres in extent, spilling over to the east side of Wadi Zarqa, housing 2,000 people and more. By 6300 BC, however, it is in an advanced state of terminal decline….

The river within Wadi Zarqa still flows but the valley sides are bare- not just around the village but as far as one can see. Soil exhaustion and erosion had devastated the farming economy of ‘Ain Ghazal. Not a single tree remains within walking distance of the town. Its people had travelled further and further every year to plant their crops and to find fodder for their goats. Yields declined, fuel became scarce and the river polluted with human waste. Infant mortality, always high, reached catastrophic proportions, so that population levels collapsed, compounded by the steady departure of people back to a life within scattered hamlets. Such is the story of all PPNB towns of the Jordan valley- complete economic collapse.” (Mithen:2003:87)

“The new architecture in western Asia had gone hand in hand with new rules and regulations for living together. These were imposed by the priests such as Lubbock had seen in ‘Ain Ghazal, or agreed upon in public meeting-houses such as that of Beidha. But no such authority or decision-making for the common good has arisen at Khirokitia. Each extended family effectively cared for itself alone- producing and storing its own food, burying its own dead, even having its own religious beliefs.

Lubbock had searched in vain for public buildings where communal planning, worship or ritual might have taken place. Neither could he find any sign of authority-figures that might have provided rules and resolved disputes. While such independent family groups had been viable when fresh water, land and firewood were in good supply, these were now seriously depleted. The result was unremitting tension and conflict in the over-populated town.” (Mithen:2003:105)

“Unlike cattle, the ultimate source of the sheep and goats, wheat and barley at Merimde, Fayum and Nabta was western Asia. There are no signs that these were independently domesticated in the Nile valley where they first appear long after farming had become established in the Jordan valley and beyond. Quite how the sheep, goats and cereals spread westwards into Africa remains unclear. Arid spells may have driven pastoralists out of the Negev and Sinai deserts towards the Nile valley. Excavations at Merimde and Fayum have recovered many types of tools that are found in western Asia, such as distinctively notched arrow points and pear-shaped mace heads. The arts of spinning and weaving also appear to have spread from the east.

Both the migration of people and of trade are likely to have played a role in the arrival of Asian-style Neolithic villages in the Nile valley, just as they did in the spread of farming into Europe. But why the goats, sheep and cereals took so long to arrive remains unclear. By 5000 BC substantial farming towns were already thriving in Europe and southern Asia, to where the sheep, goat and cereals of western Asia had spread at least two thousand years before. That had required migrants or traders to travel far greater distances than is needed to reach the Nile delta from the Jordan valley. The Sinai desert may have provided a barrier, but this could hardly have been more severe than the Iranian plateau which had to be crossed for farming to reach southern Asia.

Once present in North Africa, farming settlements similar to that of Merimde soon spread along the Nile valley.

They formed small dispersed communities with huts, storage pits and animal enclosures. It took another thousand years before more substantial settlements arose, with mud-brick houses. Soon after 3500 BC the first traces of canals are found- the beginning of an irrigation system that would be the key to crop cultivation, on which Egyptian civilisation would be based as it emerged during the next two thousand years.” (Mithen:2003:502)

“Lubbock leaves the village, returning to his lofty seat in the woods, choosing to watch village life from a distance. Within a few days he begins to understand how the village works. Each household is self-sufficient; families tend their own gardens, manage their own livestock, and make their own pottery and tools. At the same time, this household independence is balanced by a culture of hospitality, the outside fireplaces being used for communal meals.” (Mithen:2003:165)

“Acorns drop, seedlings sprout only to have their life snubbed out by the nibbling teeth of deer; any saplings that survive are soon cut and taken to the village. As time passes, Lubbock watches a complete harvest fail owing to a dry winter with late frosts, and the people reluctantly slaughter sheep and goats to survive. The friendships between households, maintained by the constant hospitality, help in times of need; when one household is short of food they can rely on gaining a share of another’s.

The overriding impression from his woodland seat is that life at Nea Nikomedeia is hard: tilling fields, weeding, watering, grinding seed, digging clay, clearing woodland. Labour appears to be in short supply as even young children are pressed into weeding and spreading muck. Lubbock recalls the hunter-gatherers of Lepenski Vir, those of La Riera, Gönnersdorf and Creswell Crags, none of whom seemed to work for more than a few hours on any one day. For them, the key to a full stomach had been knowledge, not labour: where the game would be, when the fruit would ripen, how to hunt wild boar and catch shoals of fish.

As the years pass by, Lubbock watches the construction of new houses and the number of gardens increase. Villages throughout the Macedonian plain are similarly increasing in size and soon population limits are reached. The available soils around Nea Nikomedeia cannot support more people and so a group of families leave to find new land. With a herd of goats and a straggle of piglets they head northwards, aiming to create a new settlement on the first suitable flood plain they locate.

The farmers ‘leap-frogged’ their way from one fertile plain to the next, through the Balkans and on to the Hungarian plain where new farming cultures would develop. Farming settlements were made no more than 50 kilometres from Lepenski Vir, their presence leading to an initial florescence and then to the collapse of its Mesolithic culture. Some of the Lepenski Vir people, most likely the old, elaborated their artistic traditions as a means to resist the new farmers and their way of life….

But for others, most likely the young, farming settlements provided new ideas and opportunities for trade. Lepenski Vir’s fate was inevitable: an increasing number of pottery vessels appeared amidst the hunting weapons and fishing nets; its people became seduced by the farming way of life. There were some good reasons for this: sheep, cattle, and wheat could fill the dietary gaps created by the periodic shortages of wild food that had left children undernourished. But very soon the culinary tables had turned- the wild foods became the supplements to a diet of cereals and peas.” (Mithen:2003:165-6)

“There were few clear patterns between the type of burial and type of person, in terms of age and sex. As at Oleneostrovski Mogilnik, the wealthiest individuals appeared to be those in the prime of life. So power and prestige were again largely a matter of personal achievement rather than inheritance. There were limited differences between men and women, the former more frequently buried with the flint blades and axes, while elk and auroch- (wild cattle) teeth pendants seem to have been for females alone. There are no examples of individuals with inordinate amounts of wealth or who may have been shamans or chiefs.” (Mithen:2003:174)

“Lars Larsson found disturbing evidence that the Skateholm people had fought aggressively either amongst themselves or with others. Indeed, the accumulation of evidence from cemeteries and isolated burials has shown that violence was endemic within the Mesolithic communities throughout northern Europe.

At Skateholm four individuals were found with depressed skull fractures- at some time they had been hit on the head with a blunt instrument that left a permanent dent. Such blows may have simply rendered the victims unconscious, but they could well have been fatal. Flint arrowheads had hit two others from Skateholm and still lay amid their bones when excavated by Larsson: one had been hit in the stomach, the other in the chest.

These might have been innocent hunting accidents- but that would hardly explain the fractured skulls. Some of the violence may have been ritualistic in nature. At Skateholm, a young adult female had been killed by a blow to the temple and then laid beside an older male within a single grave- perhaps a sacrifice to join her partner, perhaps the ultimate punishment for some unknown crime. But most likely explanation for the violence is that these Mesolithic communities were fighting to defend their land.

Skateholm must have been highly desirable for hunter-gatherers, with abundant supplies of food in the woodland, the marshes, the rivers, the lagoon, and the sea. When the people dispersed in the summer they would not have wished to relinquish the lagoon to unexpected strangers, or to those who lived in adjacent but less productive regions.

The majority of the head injuries had come from blows to the front and left side- the outcome of face-to-face combat with a right-handed opponent. Males were more involved in fighting than the females, having three times as many head-wounds and four times those from arrows. One can easily imagine groups returning to the lagoon as summer ended, finding uninvited occupants already present and fighting for their land.” (Mithen:2003:175)

“The common explanation among archaeologists for the growth of violence in the Mesolithic societies of northern Europe after 5500 BC concerns population pressure on diminishing resources. Ever since 9600 BC the woodlands, lagoons, rivers, estuaries, and seashores of northern Europe had provided abundant wild resources. The populations of the first settlers after the ice age and those of the Early Holocene would have expanded rapidly- they were in a Mesolithic Garden of Eden. But by 7000 BC those living in the lands of modern-day Sweden and Denmark were losing substantial areas of land to the rising sea. People were increasingly crammed into smaller and smaller territories, leading to intense competition for the best hunting, plant-gathering and- especially- fishing locations.

The economic and social problems caused by environmental change had been exacerbated, however, by a new force that had entered these people’s lives.

It was one that had already overwhelmed the occupants of Franchthi Cave and Lepenski Vir and which had originated far away in western Asia. By 5500 BC, farmers had arrived in central Europe and made contact with the indigenous people, either in person or via traded goods. The farmers’ desire for land, for women, for furs and wild game fitted neatly with the Mesolithic people’s need for new items of prestige such as polished axes in other to pursue their own internal social competition. They began to trade across a frontier- farmers to the south in what is now Poland and Germany, hunter-gatherers to the north in Denmark and Sweden. But whereas the farming settlements flourished by such contact, it caused further social disruption and economic stress for the Mesolithic people. And it would eventually lead to complete cultural collapse.” (Mithen:2003:177)

“By 6000 BC the Mesolithic people of northern Europe were listening to fire-side stories from visitors about a new people in the east, people who lived in great wooden houses and controlled the game. Soon they found their own Mesolithic neighbours using polished stone axes, moulding cooking vessels from clay and herding cattle for themselves. When farming villages arrived within their own hunting lands, Mesolithic eyes peered from behind trees at the timber long houses, the tethered cattle and the sprouting crops with mixed emotions- fear, awe, dismay, disgust.

The older generation must have struggled to understand what they saw. Although they had felled trees and built dwellings themselves, the new farmsteads were quite beyond their comprehensions. The farmers appeared intent on controlling, dominating and transforming nature….

Mesolithic dwelling required no more than promoting and combining the existing suppleness of hazel, the stringiness of willow and the sheets of birch bark that grew ready-made; a timber-framed long house, on the other hand, required nature to be torn apart and the world constructed anew.

The older men and women are likely to have retreated from the forests of central Europe, relinquishing their hunting grounds and insisting that ever more time be spent celebrating the natural world. But they sang and danced against the tide of history: the younger generation had quite different ideas….

Those who continued with their Mesolithic culture in the northern forests had to adjust their traditional hunting-and-gathering patterns. Furs, game, honey, and other forest products had to be procured for trade; the wild resources were fought over and further depleted. And as increasing numbers of women joined the farmers, perceiving agriculture as providing greater economic security for themselves and their children, there were fewer to maintain the Mesolithic populations. Both land and women became sources of tension that often boiled over into the violence so vividly documented within the Mesolithic graves.

By 5000 BC a new type of farming culture had emerged from the fringes of the Hungarian plain: the Linerbandkeramik, which archaeologists thankfully abbreviate to the LBK. It spread with astonishing speed both east and west, into the Ukraine and into central Europe. While Lubbock was canoeing towards Skateholm, the LBK farmers were crossing and clearing the deciduous woodlands of Poland, Germany, the Low Countries and eastern France.

This was a quite different type of Neolithic to that which had appeared in Greece and spread northwards through the Balkans to reach the Hungarian plain.

As their LBK name implies, these farmers decorated their pottery with bands of narrow lines; they constructed timber long houses and relied on cattle rather than sheep and goats. Nevertheless, archaeologists have traditionally assumed that the LBK farmers were direct descendants of the original immigrants from western Asia and represented a new phase of their migration across Europe.… the new farmers travelled westwards at a remarkable rate, covering 25 kilometres a generation. Just like the original immigrant farmers of Southeast Europe, they filled up each new region of fertile soils with farmsteads and villages and then leap-frogged across less favourable soils to establish a new frontier. Such speed reflects more than the success of their lifestyle- it implies an ideology of colonisation, an attraction to ‘frontier life’, similar, some have suggested, to that of the Trekboers of South Africa and the pioneers of the American West.” (Mithen:2003:178-80)

“Lubbock remains with the pine-marten furs as they are traded from group to group into northern Germany. As he travels south, the Mesolithic people seem increasingly concerned with identity and territorial boundary: each group can be identified by their distinctive clothes and hairstyles, and by the manner in which they make their tools. Some have made their harpoons straight and others curved; some have made their stone axes with parallel sides while others produce axes with a flared cutting edge. Lubbock recalls the time when the Mesolithic had begun, the time of Star Carr- when a virtual identity in human culture had existed across the whole of northern Europe. The old Mesolithic order had become fractured and would be soon be gone….

Lubbock is at the frontier- that between the LBK farmers and the remaining indigenous hunter-gatherers of the forests. The clearing is a known meeting-place, but as yet quite unmarked by human structures. Within a few generations, the farmers will build houses and surround them by a ditch. Archaeologists will eventually know their settlement as Esbeck. Some will argue that the ditch was made for defence against the remaining hunter-gatherers who had turned hostile after their Mesolithic culture had almost entirely disappeared.” (Mithen:2003:186)

“When full-scale rice farming arrived in Japan at around 500 BC, the hunting-gathering-cultivating Jomon lifestyle was replaced by a rural agricultural economy that made use of iron tools and continued into modern times. Incoming people originating in China and Korea brought this new economy to Japan. It is from these people that almost all modern-day Japanese people are descended. Because rice was unable to grow in the colder environments of northern Honshu and Hokkaido the Jomon culture survived a little longer in the north of Japan. Today, the Ainu people who maintain a hunting-and-gathering lifestyle inhabit these regions. Many believe that the Ainu are not only the cultural inheritors of the Jomon way of life, but the biological descendants of the Jomon people themselves.” (Mithen:2003:380)

“The Hassuna period, approximately 6800-5600 BC, marks the turning point of Mesopotamian prehistory. It leaves behind the world of hunter-gatherers and small farming villages and looks forward to the expansion of towns and trade. …

By 5000 BC substantial towns are found throughout the whole of the Fertile Crescent, except in the extreme southwest where those of the Jordan valley had long been abandoned. In the lands surrounding the Tigris and Euphrates a new cultural unity had emerged, combining the Hassuna and Samarra cultures. Known as the Halaf period, this lasts for a whole millennium, supported by the same crops that had sustained prehistoric farmers since the days of Jericho and Maghzaliyah: wheat and barley, peas and lentils. But a key development had occurred: the use of artificial irrigation. It had been this which enabled people to fully exploit the rich alluvial plains of southern Mesopotamia.

Although sheep and goats were pre-eminent at Sawwan, cattle were important, their significance reflected in cow figurines and pottery painted with a bull’s-head motif. As the addition of rich milk fats to human diets can increase the birth rate, cattle herding may have been a factor behind what appears to have been a population explosion.” (Mithen:2003:438-9)

What we see from the above quotes is that settlers began to over-populate every land of plenty that they came across and so the effect of settling caused overpopulation and the effect of this was the necessity to require more and more land. In other words, the idea of necessity had been effected. More people and more land meant that people in different circles ‘families’ or people one is familiar with as this originally meant, began to fight to gain new lands and keep old ones.

What we must ask therefore is, what was the story that replaced the ancient story of wakan and the universal nature of all of Nature.

Did we want this new story, or was it thrust on us, as a necessity due to the new experiences of these hungry, over-populated man-made deserts of previous-abundance?

We have seen that this event was a global one, and so we must we able to find this perspective told in myth too. How did the story of the hunter-gatherer change in order to become the settler story, that got ‘us’ to fight against ‘them’, as a way of thinking in terms of good and evil, right and wrong? And when new lands are gained by a family, how does the story intimate that the booty should be shared? Universally, individually, hierarchically? The story must reflect these behaviours. And what of God now, a God now slightly more distant from this intimate story, how does he look down upon us, across this space and time, that we have created? Let us look further at the scientific story, or evidence, as they call it, keeping these questions in our minds, and then see these ancient stories, to reconcile the two as showing the same evident ‘truth’, whilst the latter still contains ‘aletheia’ before this same ‘truth’ is framed.

02: Lets get the band back together – a limited-capital idea!

When a group of villagers come across an invader then the ‘them’ is quite obvious, but when the ‘them’ is others in the village i.e. ‘not me’, then it is not so easy to justify your loss over their gain, or your right over their lack of rights. It is also hard to get some-one else to work your land for you when they have their own land, and when a few generations have gone by, to justify why your land is still your land, when there is no more arable land left to farm within that territory and therefore the next generations land is ‘somewhere else’ or non-existent if they wish to stay.

What is needed is a story that will cohere a group of people within the village against another group of people within the village. In other words a story that will ‘Divide and Conquer’ in a self-worlded World of ‘poverty and over-population’, a world of ‘supply and demand’ not of ‘abundance and no satiety’ in a being-worlded World.

“Most important of all for the long-term evolution of the world economy were the changes in social organization that resulted from the establishment of settled agriculture. The previous communal social order was steadily replaced by a kin-ordered system that laid the basis for a new, stratified social structure. Kin groups emerged as a ‘natural’ way of assigning rights over resources, and organizing the production and storage of food, but they also generated new social institutions to deal with the ownership of property and the formal exchange of goods.

The increased volume and reliability of food supplies allowed much higher population densities and encouraged the proliferation of settled agricultural villages. Together with the new social institutions of kin-ordered societies, this, in turn, facilitated the development of non-agricultural crafts, such as pottery, weaving, jewellery and weaponry. Such specializations in their turn encouraged the beginnings of barter and trade between communities, sometimes over substantial distances.” (Knox et al:2003:121)

“Between these two types of unit, the one based on kinship and the other on common interest, there was a complex relationship. In illiterate societies few remember their ancestors five generations back, and to claim a common descent was a symbolic way of expressing a common interest, of giving it a strength it would not otherwise have. In some circumstances, however, there could be a conflict. A member of a kinship group called upon for help might not give it fully because it went against some other interest of personal relationship.

Beyond these more or less permanent minimal units there might be larger ones. All the villages of a district, or all the herding units of a grazing area, or even groups widely separated from each other, might think of themselves as belonging to a larger whole, a ‘fraction’ or ‘tribe’, which they would regard as differing from and standing in opposition to other similar groups. The existence and unity of the tribe were usually expressed in terms of descent from a common ancestor, but the precise way in which any fraction or family might be descended from the eponymous ancestor was not usually known, and the genealogies which were transmitted tended to be fictitious, and to be altered and manipulated from time to time in order to express changing relationships between the different units. Even if they were fictitious, however, they could acquire a force and strength by intermarriage within the group.

The tribe was first of all a name which existed in the minds of those who claimed to be linked with each other. It had a potential influence over their actions; for example, where there was a common danger from outside, or in times of large-scale migration. It could have a corporate spirit (‘asabiyya) which would lead its members to help each other in time of need. Those who shared a name shared also a belief in a hierarchy of honour. In the desert, the camel-breeding nomads regarded themselves as the most honourable, because their life was the freest and the least restrained by external authority.”(Hourani:1991:106-7)

“The power of such leaders and families varied across a wide spectrum. At one extreme stood leaders (shaykhs) of nomadic pastoral tribes, who had little effective power except that which was given them by their reputation in the public opinion of the group. Unless they could establish themselves in a town and become rulers of another kind they had no power of enforcement, only that of attraction, so that nomadic tribes could grow or diminish, depending on the success or failure of the leading family; followers might join or leave them, although this process might be concealed by the fabrication of genealogies, so that those who joined the group would appear as if they had always belonged to it.” (Hourani:1991:108)

“The family extended kinship groups often operate economic functions for their own benefit and such ties are a major basis for labour recruitment. Ascribed systems of social stratification focus primarily on those aspects of human experience which centre on kinship, gender, ethnicity and territorial locality. Life chances depend upon the status accorded by birth into a particular family or tribe. Under a simple form of economic organization, for example subsistence agriculture of household industry, there is little differentiation between economic roles and family roles. Pre-modern societies fuse social and political integration with kinship position, control of land, chieftainship or powerful culturally significant groups. Often peoples’ sense of self is bound up in the actualities of blood, race, language, locality, religion and tradition (Geertz 1967:168). According to one theorist, these deep-rooted sentiments stem from the feeling that, whatever may be the monetary economic advantages of the larger sphere, ultimate security, not necessarily dominated by economic forces, exists and persists within the village orbit:

‘Here there are always kinsmen and people’s of one’s own blood to whom the peasant may turn. Here is the plot of land enduring through generations. Here is the familiar world which, through lore and tradition, has nourished the peasant since childhood. Here within the village is an emotional form of security found elsewhere.’ (Fuller 1969: 116)

These primordial instincts can be powerful and resistant to change.

As Max Weber claimed, social action includes both ‘failure to act and passive acquiescence’ (Roth and Wittich 1968:22).

When industrialization occurs only in villages or when villages are built around paternalistic industrial enterprises ‘many ties of community and kinship can be maintained under industrial conditions’ (Smelser 1966:35). The difficulty with such communities is that political authority is coterminous with kinship relations and, therefore, can inhibit reform and development.” (Deegan:2009:10-11)

“There is a strong relationship between families and social capital. Families in the first instance constitute the most basic cooperative social unit, one in which mothers and fathers need to work together to create, socialize, and educate children. James Coleman, the sociologist who was most responsible for bringing the term social capital into broader use, defined it as “the set of resources that inhere in family relations and in community social organizations and that are useful for the cognitive or social development of a child.” Cooperation within families is facilitated by the fact that it is underpinned by biology: all animals favour kin and are willing to undertake large one-way transfers of resources to genetic relatives, in ways that vastly increase the chances of reciprocity and long-term cooperation within kin groups.

The propensity of family members to cooperate facilitates not just raising of children, but other sorts of social activities like running businesses. Even in today’s world of large, impersonal, bureaucratic corporations, small businesses, most of them run by families, account for as much as 20 percent of private sector employment in the American economy and are critical as incubators of new technologies and business practices.

On the other hand, excessive dependence on kinship ties can produce negative consequences for the broader society outside the family. Many cultures, from China to Southern Europe to Latin America, promote what is called “familism”, that is, the elevation of family and kinship ties above other sorts of social obligations. This produces a two-level morality, wherein the level of moral obligation to public authority of all sorts is weaker than that reserved for kin. In the case of a culture like that of China, familism is promoted by the prevailing ethical system, Confucianism. In this type of culture, there is a high degree of social capital inside families but a relative paucity of social capital outside kinship.” (Fukayama:1999:36-7)

“A popular saying in Brazil is that there is one morality for the family and another for the street.” (Fukayama:1999:241)

So, as communities started to gain, so people wanted to place themselves above, others. This initial mode of divide and conquer, and as we saw still continues to this day, is called ‘familism’ or ‘kin-groups’.

As no longer was the sacred blood of the spirit of God flowing through us all, through the trees and animals, clouds and stars in the ‘Great Brown River’ in the experience of these new beings-for-itself, so ‘their’ blood was renamed in its lingual meaning to that we know today in the term, ‘blood is thicker than water’. That is the water of the ‘Great Brown River’ that brings us life.

Family, then, is the first system that divides the whole peoples into those who have and those who do not, as soon as there is something to have due to the nature of a settlement, that is settling (therefore the requirement of the legal interpretation of this same word). And that this system, still holds sway over much of the organisation of peoples in the world today. Today, in the west we more often call familism- ‘nepotism’. It is also still strongly in our language, with most peoples surnames denoting the family trade or work that they as a kinship group undertook within the village.

As we shall see below, familism, whilst being a very strong form of social organisation up to a certain amount of peoples, becomes weakened by other greater stories, whereupon it begins to divide against itself. But before we look at these let us look more closely at just what the story of family provides the story-teller and its adherence.

If we remember the sacred and empowering feelings that invisibly cohered the Aborigines of Australia and the North-American Indians together, and Durkheims observation that it is society itself that creates this experience into the story of a ‘Greater Being’ or power as ‘wakan’. Then what shall we call the ‘force’ of this ‘greater being’ namely family? As we have seen the language of the word blood changes its meaning to actual blood that is now physically, not psychically, the ‘invisible force’ that runs through a select group of people. But for our purposes I would like to call it something else, a term that will enable us to see this invisible blood alongside another invisible blood that we will meet soon, due to its creation from this familial spirit and its settling way of life (Ham).

The term I would like to give this blood is that of ‘Social Capital’, as used by Fukayama above.

Capital comes from the Latin caput, meaning, ‘a head’ and in regards to the present context it therefore refers to the ‘head’ of the family, who by use of the story of familism uses these invisible bonds to get his ‘blood’ to work in his fields for him, or make pots for trade for him, etc, in order to create wealth, that is to say ‘financial’ Capital. Capital in this context, as money, comes from the Latin capitalis meaning ‘chief’, revealing the intimate connection. In other words, to witness the lingual change from social family capital to that which produced financial capital, we may see that the ‘head’ of the family in the village that amassed the most capital over all of the other families, became ‘capital’, ‘head’ of the village. Not due to his social capital but due to his capital.

But here-in lies a pertinent point. Capital is a thing, that is a piece of matter. Yes you can use your capital in order to borrow more capital, but you must have capital in order to do this. You must have some-thing that is of value. The repercussion of this is quite simply one of finity. That is to say the physical World is finite. There is only so much capital to be had, and therefore so much social capital, if this is the basis of your being The Capital, leader, of your family.

On the other hand, social capital is not a thing, it is an invisible experience that comes from the magical inner world. Yes, we are back to the magic horse (social capital) and the iron fish (capital). In other words I can love each of my family members as much as I want, no matter how many of them there are (infinitely), I can hate each of my enemies as much as I want, no matter how many of them there are (infinitely), I can be infinitely, envious, grateful, awe-full, powerful, happy, sad, ambivalent, etc, etcetera, with my social capital infinitely, but I cannot be so with my capital- my things, as they are finite.

As we have seen, the social capital of the hunter-gatherer, of the cave-man that we are following through the last 20,000 years up to the present and into the future, was one of social capital for all, and capital was to be laughed at, and its ‘possessor’ or ‘story-teller’ was to be killed. For the familist who relies on the self-interest of the individual in following the common interest of gain, capital is infinite whilst hunger for capital is infinite, and he must struggle to maintain the subjective infinite desires of his subjects, with the finite realities of objective Nature, which he turns to his will. For our cave-man social capital has infinity in its Nature, it is an infinite circle,- an openness- a being-in-Being. For the leader of these beings-for-itself, social capital therefore must either become the infinite resource that he can always call upon in a finite circle of resources, or the finite circle or resources, must become what he can always call upon in an infinite circle of social desires. From one perspective he can have infinite capital, from the other he can be only become poorer and poorer until he is usurped. a closedness that requires protection, i.e. a garment, to defend itself from those other people in their finite circles.

It is then resultant from standing in these finite circles, that the conditions of loss and gain, of us and them, of mine and an-others come into existence. Within the village, as we have seen, this was narrated by the story of family. Outside of the circle of the village, as we shall see throughout this book, it was called species identity, that is race, colour, creed, and later on nationality. For now I wish to bring your attention to exactly how the mindset of these people in circles, these pilgrims to the self, change as a consequent to their new ontological perspective, now that they are within a circle greater than themselves alone, that is greater than a single individual but lesser than the individual race of Adam, the great single individual- ‘humankind.

“All people in all continents at 20,000 BC were members of Homo sapiens, a single and recently evolved species of humankind. As such, they shared the same biological drives and the means to achieve them- a mix of co-operation and competition, sharing and selfishness, virtue and violence. All possessed a peculiar type of mind, one with an insatiable curiosity and new-found creativity. This mind- one quite different to that of any human ancestor- enabled people to colonise, to invent, to solve problems, and to create new religious beliefs and styles of art. Without it, there would have been no human history but merely a continuous cycle of the adaptation and readaptation to environmental change that had begun several million years ago when our genus first evolved. Instead, all of these common factors combined, engaging with each continent’s unique conditions and a succession of historical contingencies and events, to create a world that included farmers, towns, craftsmen and traders. Indeed, by 5000 BC there was very little left for later history to do; all the groundwork for the modern world had been completed. History had simply to unfold until it reached the present day.” (Mithen:2003:505-6)

What we must look at then in order to discover why settled man became so curious and creative is the situation and the subsequent perspective of a peoples who are now in a land of supply and demand, due to the lack of resources that the life style of settling produces by over-population and environmental degradation.

03: The great war of the electrified mice

This is a true story about a real scientist and some real mice.

Once upon a time a mouse was sitting in a cage. A scientist came along and decided to experiment on it in order to understand its reaction to stress.

What she did first of all was to electrify one half of the cage. To this experience of pain coming from its urgrund, the mouse got off its lazy arse, at great speed I might add, and, inspired by the pain, created the curiosity of seeing if all the cage was this painful to try and sit peacefully in, he strategically moved to the other side, using the technique of jumping. This being the most efficient method. Anyway, once the mouse had learnt this technique to alleviate its stress the scientist decided to electrify both sides of the cage to see what it would now do.

The mouse tried jumping from one side to the other until it realised that it had no strategy to escape the stress of the situation and so instead it went into a corner, curled up into a ball, and began to lose its fur. Ah, poor little mouse.

The scientist then put another mouse into the mix. Once again, she electrified half of the cage and the mice learnt to jump to the other half. Once again, she then electrified both sides. But, instead of finding that each mouse chose a corner each, huddled up in it and started losing its fur, they started to attack each other!

In other words, when an animal is stressed it does what it can to relieve the situation. Unfortunately, due to the lack of intelligence of the animal, the cause and effect, side of things, i.e. for the mouse; “Is it actually this other mouse causing the effect of electrifying the cage?”, wasn’t really thought out before it came to blows. Blows one might add, that would be totally fruitless in regard to solving the situation that the mice found themselves in, but were rational based upon the physical evidence. Based upon this reasoning however, and the constant pain accompanying it, the mouse saw a cause and effected a solution consequent to it. If it had said that it was God punishing him, then he would have been closer to the truth (the unconcealedness of the human-Being in the white coat) and if he had said that it was a force- wakan- running through the cage he would have been closer to the truth also, but that would have been unreasonable to the other mouse who believed only in experience and il poche’d their experience when it came to looking out of the cage and seeing a Being in a white coat. Food for thought perhaps.

Anyway these two mice now define an invisible circle ontologically called enemy, called other, and attacks it to end its suffering. The victorious mouse found that killing the other mouse could indeed end his suffering. How? By standing on top of the dead mouse corpse it reduced the amount of electricity going through its own body, it became insulated- that is to say closed off- from the pain, by the suffering of another of its own species. It is rumoured that the victorious mouse was an American mouse and the loser was a European mouse but that is another story.

In the same manner then, at the dawn of civilization, mankind finds that, not nature, but he himself, has created a cage, out of an insurance policy based on wild grains, that by becoming non-brittle, domesticate us. That is to say, we call non-brittle grains ‘domesticated’ over ‘wild’, yet in truth it is the grain that is now roaming the Earth freely, and we ‘ourselves’ that have become domesticated by it. As humans now tell an unquestioned story that we are above nature, and have our own separate nature consequently, we have told the story of the grain as domesticated by us, because it makes us feel more powerful in some invisible inner world way. So too do we now tell stories of the superiority of one’s own human-nature over another’s human-nature because it simply allows us to feel more powerful in some invisible inner world way, and this story allows us to experience others as inferior, and hence less valuable, and so our behaviour begins to reflect this belief. The word for this is belief system is ‘Justified’.

The Mouse then, has been electrified into seeing the world in terms of space and time in accordance with the scientists view of the world. No longer is the world a safe place, it is now only safe at a certain time in a certain place, and therefore, by necessity the mouse must not only perceive the outer world that way but also his inner world and this will change his behaviour. The inner world experience is now one of pleasure and pain, not abundance without any opposite.

In a world of pleasure and pain, (an animal world), the accompanying intimate feelings are those of hope and fear and when another animal enters that world it also enters that same space and time. When the second mouse arrives and the pain increases in space and time, then both mice attack any cause that they can see might effect an end to that pain. There solution is unreasonable and will not result in the required goal, but they continue to behave in such a manner. When a group of people cause their own pleasure and it results in pain over space and time and then another group of people is seen in this same world, then they both attack any cause that they can see might effect an end to that pain. There solution is unreasonable and will not result in the required goal, but they continue to behave in such a manner, unable to see that the ‘person in white coat pressing the button’ is their own way of perception, desires as justified beliefs.

Unable to comprehend this greater truth- the unconcealed nature of the being-for-itself, dons a new veiled garment imperceptibly over the two thousand years that it took to weave it between 5500 B.C. and 3500 B.C, he used his power, to escape the pain it was causing each individual in the only way he knows how. Divide and conquer, fight the other mice and stand upon their finite corpses as capital.

This new dance of ‘us’ and ‘them’, therefore becomes a ritual that solves the problem of desertification of the landscape and over population too, much as the magical words of the weather-man resulted in less weekend rain as well as the social capital of rush hour being turned into alimental communal travel

The by-product of this dance, or reason, is that the supply of capital goes up as demand for capital goes down, due to loads of people being killed, that were once alive. The dead cannot eat, they cannot fight, they cannot claim property rights over land they cannot work, but we can take the efforts of their work and reduce our pain by standing on their corpses- pleasure. Therefore the story of the victors must be true because they live to right it.

Meanwhile ‘concealed’ underneath this ‘truth’ and its subsequent justified behaviour lies the ontological electrified cage, the mechanism of the insurance policy, settling, which is still in place, still exists and hence, given time will result in over population of the cage, causing supply problems once again due to increased demand in the form of over-population, as natural population control is no longer enforced by the necessity of carrying only one baby at a time when living as a hunter-gatherer, not a settler, and so the Great War of the Electrified Mice will forever continue under the unreasonable reasons for ‘Divide and Conquer’.

As we saw above, for the first civilizations, this electrified cage became the root of their demise.

As we will see, for every civilization that came after it, it was the root of its demise. As we will see, for every civilization today, it is the root of its existence and its coming demise, unless it changes its story.

It may seem that linking an experiment with mice to human civilization is a bit of a weak one, and so I would like to add two addendums to strengthen my case.

The first is that every 5 seconds a mouse dies. Why? Because mice are so similar in their genetic make-up to man- 97% similar, that they are used by modern science in countless biological and psychological experiments, from new skin products to curing cancer, from maze solving to office efficiency. So the connection I am making with the above story is resultant from actual experiments of behavioural psychology itself, and a mouse was chosen because, primarily, of its similarity to ourselves genetically.

The second illustrative point, is, I am afraid, both true and horrendous. Imagine the Great War of the Electrified Mice, actually taking place with human-beings. Would you, if you put a load of humans in a cage and caused that cage to be pain causing, see the response of the mice where the people piled themselves ever higher upon the corpses of the others in order to escape the pain. Well in World War II this experiment was actually practiced for sociological reasons other than those we now speak of, at least in the minds of those conducting the experiment, but ontologically for the same reason as we now speak of.

It did so in the form of the concentration camps such as Auschwitz. In these camps soldiers who were being electrified by the lack of supply to their demand were convinced that the mice responsible were called Jews, and could be recognised by certain physical signs to denote their difference. They could also been seen to be holding a lot of the money that rationally caused the lack of supply to their demands of hunger (pain). These Jewish mice were then divided from the human species as a whole and conquered by being put to death.

Once all the German-Jewish mice, who were also families as well as Jews, were collected together, they were taken to concentration camps, where they were sub-divided once again, From German into German-Jews, into German-Jews who would be useful to the German (non-Jewish) state, i.e. the educated- group, and the strong- group, over the kinship-group. The German-Jews who were not useful to the German (non-Jews), because they were the weak or useless, i.e. the old, the women, the children, i.e. those not in demand, because they could not supply, were put into the ‘to-being-killed’- group

These weak and ‘unnecessary’ for my purpose were then taken to a shower room, an electrified cage, where Xyclon B, a poisonous and invisible gas (force), was pumped in and they were all killed.

What the German (but not Jewish) soldiers discovered when they opened the doors was not a collection of bodies all in the corners of the room, who had given up and let it happen. Instead they found a pyramid of bodies, where children had climbed over women, where the old had climbed over children, where all had fought each other to get to the top where the gas was less, so that they may live longer, despite rationally knowing that it would not, in the long term, help anyone including themselves.

In other words, it is necessity that is the mother of invention. It is pain that calls the human to invent, to be curious about those ‘things’ around him and how they can be inventively used towards his own ends. It was settling, over-population and desertification of the environment that created the pain, the cause of the effect. It was the greed of some Jews throughout history that caused the pogroms of all Jews throughout history. It was the gain of capital by the few by using the social capital of the many, that the social capital of the many became depleted (pogroms) by another group of capitalists ‘chiefs’, using the power of another group of social capital (Germans in this case, but throughout history pretty much every other circle). It was the closing of the circle that created the electrification, and it was the being-for-itself that created the circle, therefore the climbing on top of each other, ‘inventiveness’ of a story called ‘family’, and subsequently, as we shall see, of the invention of civilization that created a new language for its own new story. What the story and perspective of the German peoples was at this time will be shown later to be the root cause of The Holocaust, and it will also be shown to be our own perspective!

This new ontological outlook then we will call political philosophy, that is to say, once a human-being becomes a type of person different from another he becomes a part of a group of people who think the same way, and apart of a group of people who do not. When underpinned by necessity, i.e. when the urgrund of settling, being-for-itself, has created necessity in order to survive by desertification, the philosophy of each peoples (in Greek polis, from where we derive the word politics) becomes, ‘the philosophy you can afford’, in order to live (a necessity). We will see great atrocities done in the name of acquiring the power to have the ‘right’ to a political philosophy that can be afforded in a world now based upon survival. A world we have forced ourselves to live in for only the last 5,000 years. It is called the history of civilization.

04: Being-for-others

“As a temporal-spatial object in the world, as an essential structure of a temporal-spatial situation in the world, I offer myself to the Other’s appraisal. This also I apprehend by the pure exercise of the cogito. To be looked at is to apprehend oneself as the unknown object of unknowable appraisals- in particular, of value judgement. But at the same time that in shame or pride I recognize the justice of these appraisals, I do not cease to take them for what they are- a free surpassing of the given toward possibilities. A judgement is the transcendental act of a free being. Thus being-seen constitutes me as a defenceless being for a freedom which is not my freedom. It is in this sense that we can consider ourselves as “slaves” in so far as we appear to the Other. But this slavery is not a historical result- capable of being surmounted- of a life in the abstract form of consciousness. I am a slave to the degree that my being is dependent at the centre of a freedom which is not mine and which is the very condition of my being. In so far as I am the object of values which come to qualify me without my being able to act on this qualification or even to know it, I am enslaved. By the same token in so far as I am the instrument of possibilities which are not my possibilities, whose pure presence beyond my being I can not even glimpse, and which deny my transcendence in order to constitute me as a means to ends of which I am ignorant- I am in danger. This danger is not an accident but the permanent structure of my being-for-others.” (Sartre:2003:291)

“In the first place, he is the being toward whom I do not turn my attention. He is the one who looks at me and at whom I am not yet looking, the one who delivers me to myself as unrevealed but without revealing himself, the one who is present to me as directing at me but never as the object of my direction; he is the concrete pole (though out of reach) of my flight, of the alienation of my possibles, and of the flow of the world toward another world which is the same world and yet lacks all communication with it. But he can not be distinct of them; he haunts this flow not as a real or categorical element but as a presence which is fixed and made part of the world if I attempt to “make-it-present” and which is never more present, more urgent than when I am not aware of it. For example if I am wholly engulfed in my shame, the Other is the immense, invisible presence which supports this shame and embraces it on every side; he is the supporting environment of my being-unrevealed. Let us see what it is which the Other manifests as unrevealable across my lived experience of the unrevealed.

First the Other’s look as the necessary condition of my objectivity is the destruction of all objectivity for me. The Other’s look touches me across the world and is not only a transformation of myself but a total metamorphosis of the world. I am looked-at in the world which is look-at. In particular the Other’s look, which is a look-looking and not a look-looked at, denies my distances from objects and unfolds its own distances. This look of the Other is given immediately as that by which distance comes to the world at the heart of a presence without distance. I withdraw; I am stripped of my distanceless presence to my world, and I am provided with a distance from the Other. There I am fifteen paces from the door, six yards from the window. But the Other comes searching for me so as to constitute me at a certain distance from him. As the Other constitutes me as at six yards from him, it is necessary that he be present to me without distance. Thus within the very experience of my distance from things and from the Other, I experience the distanceless presence of the Other to me.

Anyone may recognize in this abstract description that immediate and burning presence of the Other’s look which has so often filled him with shame. In other words, in so far as I experience myself as looked-at, there is realized for me a trans-mundane presence of the Other. The Other looks at me not as he is “in the midst of” my world but as he comes toward the world and toward me from all his transcendence; when he looks at me, he is separated from me by no distance, by no object of the world- whether real or ideal- by no body in the world, but the sole fact of his nature as Other. Thus the appearance of the Other’s look is not an appearance in the world– neither in “mine” nor in the “Other’s”- and the relation which unites me to the Other can not be a relation of exteriority inside the world. By the Other’s look I effect the concrete proof that there is a “beyond the world”. The Other is present to me without any intermediary as a transcendence which is not mine. But this presence is not reciprocal. All of the world’s density is necessary in order that I may myself be present to the Other. An omnipresent and inapprehensible transcendence, posited upon me without intermediary as I am my being-unrevealed, a transcendence separated from me by the infinity of being, as I am plunged by this look into the heart of a world complete with its distances and its instruments- such is the Other’s look when first I experience it as a look.

Furthermore by fixing my possibilities the Other reveals to me the impossibility of my being an object except for another freedom. I can not be an object for myself, for I am what I am; thrown back on its own resources, the reflective effort toward a dissociation results in failure; I am always reapprehended by myself. And when I naively assume that it is possible for me to be an objective being without being responsible for it, I thereby implicitly suppose the Other’s existence; for how could I be an object if not for a subject. Thus for me the Other is first the being for whom I am an object; that is, the being through whom I gain my objectness. …

At the same time I experience the Other’s infinite freedom.

It is for and by means of a freedom and only for and by means of it that my possibilities can be limited and fixed. A material obstacle can not fix my possibilities; it is only the occasion for my projecting myself toward other possibles and can not confer upon them an outside. To remain at home because it is raining and to remain at home because one has been forbidden to go out are by no means the same thing. In the first case I myself determine to stay inside in consideration of the consequences of my acts; I surpass the obstacle “rain” toward myself and I make an instrument of it. In the second case it is my very possibilities of going out of or staying inside which are presented to me as surpassed and fixed and which a freedom simultaneously foresees and prevents. It is not mere caprice which causes us often to do very naturally and without annoyance what would irritate us if another commanded it. This is because the order and the prohibition cause us to experience the Other’s freedom across our own slavery. Thus in the look the death of my possibilities causes me to experience the Other’s freedom. This death is realized only at the heart of that freedom; I am inaccessible to myself and yet myself, thrown, abandoned at the heart of the Other’s freedom….

Thus through the look I experience the Other concretely as a free, conscious subject who causes there to be a world by temporalizing himself toward his own possibilities. That subject’s presence without intermediary is the necessary condition of all thought which I would attempt to form concerning myself. The Other is that “myself” from which nothing separates me, absolutely nothing except his pure and total freedom; that is, that indetermination of himself which he has to be for and through himself.” (Sartre:2003:293-5)

“… the Other’s presence in his look-looking can not contribute to reinforce the world, for on the contrary it undoes the world from me when it is relative and when it is an escape toward the Other-as-object, reinforces objectivity. The escape of the world and of my self from me when it is absolute and when it is effected toward a freedom which is not mine, is a dissolution of my knowledge. The world disintegrates in order to be reintegrated over there as a world; but this disintegration is not given to me; I can not know it nor even think it. The presence to me of the Other-as-a-look is therefore neither a knowledge nor a projection of my being nor a form of unification nor a category. It is and I can not derive it from me.” (Sartre:2003:296)

“But these remarks can be generalized; it is not only Pierre, Rene, Lucien, who are absent or present in relation to me on the ground of original presence, for they are not alone in contributing to situate me; I am situated also as a European in relation to Asiatics, or to Negroes, as an old man in relation to the young, as a judge in relation to delinquents, as a bourgeois in relation to workers, etc. In short it is in relation to every living man that every human reality is present or absent on the ground of an original presence. This original presence can have meaning only as a being-looked-at or as a being-looking-at; that is, according to whether the Other is an object for me or whether I myself am an object-for-the-Other. Being-for-others is a constant fact of my human reality, and I grasp it with its factual necessity in every thought, however slight, which I form concerning myself. Wherever I go, whatever I do, I only succeed in changing the distances between me and the Other-as-object, only avail myself of paths toward the Other. To withdraw, to approach, to discover this particular Other-as-object is only to effect empirical variations on the fundamental theme of my being-for-others. The Other is present to me everywhere as the one through whom I become an object. Hence I can indeed be mistaken concerning the empirical presence of an Other-as-object whom I happen to encounter on my path.” (Sartre:2003:303)

“It is indubitable that at present I exist as an object for some German or other. But do I exist as a Frenchman, as a Parisian in the indifferentiation of these collectivities or in my capacity as this Parisian around whom the Parisian population and the French collectivity are suddenly organized to serve for him as ground? On this point I shall never obtain anything but bits of probable knowledge although they can be infinitely probable.

We are able to now to apprehend the nature of the look.

In every look there is the appearance of an Other-as-object as a concrete and probable presence in my perceptive field; on the occasion of certain attitudes of that Other I determine myself to apprehend—through the shame, anguish, etc.- my being-looked-at. This “being-looked-at” is presented as the pure probability that I am at present this concrete this– a probability which can derive its meaning and its very nature as probable, only from a fundamental certainty that the Other is always present to me inasmuch as I am always for-others. The experience of my condition as man, as an object for all other living men, as thrown in the arena beneath millions of looks and escaping myself millions of times- this experience I realize concretely on the occasion of the upsurge of an object into my universe if this object indicates to me that I am probably an object at present functioning as a differentiated this for a consciousness. The whole phenomenon, we call it the look. Each look makes us feel concretely-and in the indubitable certainty of the cogito– that we exist for all living men; that is, that there are (some) consciousness for whom I exist. We put “some” between parentheses to indicate that the Other-as-subject present to me in this look is not given in the form of plurality any more than as unity (save in its concrete relation to one particular Other-as-object). Plurality, in fact, belongs only to objects; it comes into being through the appearance of a world-making For-itself. The being-looked-at, by causing (some) subjects to arise for us, puts us in the presence of an unnumbered reality.

By contrast, as soon as I look at those who are looking at me, the other consciousnesses are isolated in multiplicity. On the other hand if I turn away from the look as the occasion of concrete proof and seek to think emptily of the infinite subject which is never an object, then I obtain a purely formal notion which refers to an infinite series of mystic experiences of the presence of the Other, the notion of God as the omnipresent, infinite subject for whom I exist. But these two objectivations, the concrete, enumerating objectivation and the unifying, abstract objectivation, both lacked proved reality- that is, the prenumerical presence of the Other.” (Sartre:2003:304-5)

“Therefore what I apprehend as real characteristics of the Other is a being-in-situation. In fact I organize him in the midst of the world in so far as he organizes the world toward himself; I apprehend him as the objective unity of instruments and of obstacles…

Thus the world announces the Other to me in his totality and as a totality. To be sure, the announcement remains ambiguous. But this is because I grasp the order of the world toward the Other as an undifferentiated totality on the ground of which certain explicit structures appear. If I could make explicit all the instrumental complexes as they are turned toward the Other (that is, if I could grasp not only the place which the hammer and the nails occupy in this complex of instrumentality but also the street, the city, the nation, etc.), I should have defined explicitly and totally the being of the Other as object.” (Sartre:2003:316)

“Does this mean that we must grant that the Behaviorists are right? Certainly not. For although the Behaviorists interpret man in terms of his situation, they have lost sight of his characteristic principle, which is transcendence-transcended. In fact if the Other is the object which can not be limited to himself, he is also the object which is understood only in terms of his end. Of course the hammer and the saw are not understood any differently. Both are apprehended through their function; that is, through their end. But this is exactly because they are already human. I can understand them only in so far as they refer me to an instrumental-organization in which the Other is the centre, only in so far as they form a part of a complex wholly transcended toward an end which I in turn transcend. If then we can compare the Other to a machine, this is because the machine as a human fact presents already the trace of a transcendence-transcended, just as the looms in a mill are explained only by the fabrics which they produce. The Behaviorist point of view must be reversed, and this reversal, moreover will leave the Other’s objectivity intact. For that which first of all is objective- what we shall call signification after the fashion of French and English psychologists, intention according to the Phenomenologists, transcendence with Heidegger, or form with the Gestalt School—this is the fact that the Other can be defined only by a total organization of the world and that he is the key to this organization. If therefore I return from the world to the Other in order to define him, this is not because the world would make me understand the Other but because the Other-as-object is nothing but a centre of autonomous and intra-mundane reference in my world.

Thus the objective fear which we can apprehend when we perceive the Other-as-object is not the ensemble of the physiological manifestations of disorder which we see or which we measure with sphygmograph or a stethoscope. Fear is a flight; it is a fainting. These phenomena themselves are not released to us as a pure series of movements but as transcendence-transcended: the flight or the fainting is not only the desperate running through the brush, nor that heavy fall on the stones of the road; it is the total upheaval of the instrumental-organization which had the other for its centre. This soldier who is fleeing formerly had the Other-as-enemy at the point of his gun, The distance from him to the enemy was measured by the trajectory of his bullet, and I too could apprehend and transcend that distance as a distance organized round the “soldier” as centre. But behold now he throws his gun in the ditch and is trying to save himself. Immediately the presence of the enemy surrounds him and presses in upon him; the enemy, who had been held at a distance by the trajectory of the bullets, leaps upon him at the very instant when the trajectory collapses; at the same time that land in the background, which he was defending and against which he was leaning as against a wall, suddenly opens fan-wise and becomes the foreground, the welcoming horizon toward which he is fleeing for refuge. All this I establish objectively, and it is precisely this which I apprehend as fear. Fear is nothing but a magical conduct tending by incantation to suppress the frightening objects which we are unable to keep at a distance. It is precisely through its results that we apprehend fear, for it is given to us a new type of internal haemorrhage in the world—the passage from the world to a type of magical existence.” (Sartre:2003:318-9)

“Nevertheless as the Other is thus given, he is given in what he is. Character is not different from facticity—that is, from original contingency. We apprehend the Other as free, and we have demonstrated above that freedom is an objective quality of the Other as the unconditioned power of modifying situations. This power is not to be distinguished from that which originally constitutes the Other and which is the power to make a situation exist in general. In fact, to be able to modify a situation is precisely to make a situation exist. The Other’s objective freedom is only transcendence-transcended; it is, as we have established, freedom-as-object…Although the Other’s anger appears to me always as a free-anger (which is evident by the very fact that I pass judgement on it) I can always transcend it—i.e., stir it up or calm it down; better yet it is by transcending it and only by transcending it that I apprehend it. Thus since the body is the facticity of the transcendence-transcended, it is always the body-which-points-beyond-itself; it is at once in space (it is the situation) and in time (it is freedom-as-object). The body-for-others is the magic object par excellence. Thus the Other’s body is always “a body-more-than-body” because the Other is given to me totally and without intermediary in the perpetual surpassing of its facticity. But this surpassing does not refer to me a subjectivity; it is the objective fact that the body—whether it be as organism, as character, or as tool—never appears to me without surroundings, and that the body must be determined in terms of these surroundings. The Other’s body must not be confused with his objectivity. The Other’s objectivity is his transcendence as transcended. The body is the facticity of this transcendence. But the Other’s corporeality and objectivity are strictly inseparable.” (Sartre:2003:374)

“I exist my body: this is its first dimension of being. My body is utilized and known by the Other: this is its second dimension. But in so far as I am for others, the Other is revealed to me as the subject for whom I am an object. Even there the question, as we have seen, is of my fundamental relation with the Other. I exist therefore for myself as known by the Other—in particular in my very facticity. I exist for myself as a body known by the Other. This is the third ontological dimension of my body….

With the appearance of the Other’s look I experience the revelation of my being-as-object; that is, of my transcendence as transcended. A me-as-object is revealed to me as an unknowable being, as the flight into an Other which I am with full responsibility. But while I can not know nor even conceive of this “Me” in its reality, at least I am not without apprehending certain of its formal structures. In particular I feel myself touched by the Other in my factual existence; it is my being-there-for-others for which I am responsible.” (Sartre:2003:375)

“The experience of my alienation is made in and through affective structures such as, for example, shyness. To “feel oneself blushing”, to “feel oneself sweating,” etc., are inaccurate expressions which the shy person uses to describe his state; what he really means is that he is vividly and constantly conscious of his body not as it is for him but as it is for the Other. This constant uneasiness, which is the apprehension of my body’s alienation as irremediable, can determine psychoses such as ereutophobia (a pathological fear of blushing); these are nothing but the horrified metaphysical apprehension of the existence of my body for the Others. We often say that the shy man is “embarrassed by his own body.” Actually this expression is incorrect; I can not be embarrassed by my own body as I exist it. It is my body as it is for the Other which may embarrass me. Yet there too the expression is not a happy one, for I can be embarrassed only by a concrete thing which is present inside my universe and which hinders me as I try to use other tools. Here the embarrassment is more subtle, for what constrains me is absent. I never encounter my body-for-the-Other as an obstacle; on the contrary, it is because the body is never there, because it remains inapprehensible that it can be constraining. I seek to reach it, to master it, by making use of it as an instrument- since it is also given as an instrument in a world– in order to give it the form and the attitude which are appropriate. But it is on principle out of reach, and all the acts which I perform in order to appropriate it to myself escape me in turn and are fixed at a distance from me as my body-for-the-Other. Thus I forever act “blindly”, shoot at a venture without ever knowing the results of my shooting. This is why the effort of the shy man after he has recognized the uselessness of these attempts will be to suppress his body-for-the-Other. When he longs “not to have a body anymore”, to be “invisible”, etc., it is not his body-for-himself which he wants to annihilate, but this apprehensible dimension of the body-alienated.

The explanation here is that we in fact attribute to the body-for-the-Other as much reality as to the body-for-us.